Pin

Pin

Cindy Rollins, mom of nine and “Mama of Morning Time” (so-named by me!), is back on the podcast this week to chat about Stratford Caldecott’s Beauty in the Word — specifically the portion on grammar, or what Caldecott calls “remembering.” Join us as we chat about anamnesis, what it is and how it is alike and different what we already associate with memory. Listen for:

- The idea of anchoring or tethering our children to a cultural heritage.

- What are some Morning Time elements that help to convey this cultural heritage.

- How Cindy handles the aspects of our heritage that are not positive or admirable.

- The connection between language and memory and how language helps form relationships with ideas.

- How technology is both a blessing and a curse when it comes to our efforts to be people who practice Remembering.

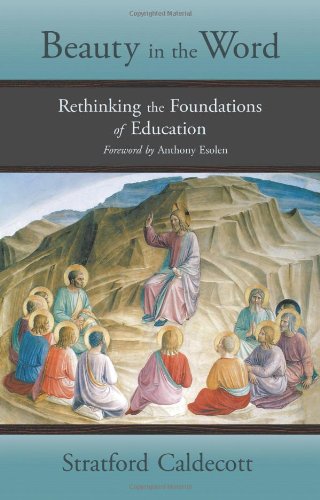

Pam: This is your morning basket, where we help you bring truth, goodness, and beauty to your homeschool day. Hi everyone. And welcome to episode 65 of the, your morning basket podcast. I’m Pam Barnhill, your host, and I am so happy that you’re joining me here today. Well, today is our final archive episode of the podcast. These are episodes that first appeared on the homeschool solution show in 2018, and we are bringing them over into the cannon. So to speak of your morning basket, and we’ve kind of saved. One of the best for last this episode is with Cindy Rollins, who I like to call the mama of morning time. She has turned an entire generation of homeschool moms onto the concept of doing morning, time or morning basket in their home. And I wanted to have Cindy on to talk about a book that is fascinating to both of us. This is Stratford Caldicot. It’s beauty in the word. If you haven’t read this one, I highly recommend it. And today we’re going to be talking about grammar as remembering, and it’s kind of a concept that Caldicot takes a little bit of a different take on than is normally heard about in classical circles.

So some of the concepts we’re going to cover are the idea of anchoring are tethering our children to a cultural heritage and how you can use morning time to do that. Why is this important? We’re also going to be talking about the connection between a language and memory and how language helps form relationships with ideas. It’s a really wonderful conversation. I think you’re going to enjoy it and we’ll get on with it right after this word from our sponsor.

This episode of the, your morning basket podcast is brought to you by a month of mourning time. Now a month of morning, time is our special sample set of warning time plans. And it’s three whole weeks of morning time plan scheduled out for you, but knowing how homeschooling is and how we often have things that come up in life, we don’t want to stress you out.

So we call this a month of morning time. You can stretch those three weeks out into filling up an entire month. Now there’s also a loop schedule in this special set of morning time plans that you can follow as well inside the set of plans, we have a lovely selection of different things you can add to your morning time, some bedtime Nat, a whole bunch of information about the Bach and the Brandenburg concertos,

some chalk pastel art, and a little bit about some really great artists like Michelangelo and DaVinci. There are so many wonderful things in here. Just a lovely collection of beautiful things to add to your morning time, all laid out for you all ready to go. All you have to do is collect a few books from your library. So if you are interested in downloading this sample set of morning time plans,

head on over to Pam barnhill.com forward slash month, or click on the show notes for this episode of the podcast. And now on with the show, Cindy Is the mother of nine grown children with a passion for equipping families to practice morning, time and homeschool for the long haul. The recipient of the 2016 Russell Kirk pie day. A prize Cindy is the author of mere motherhood,

as well as a handbook to morning time. She joins us on this episode of the podcast to talk about mourning time and remembering, Hey Cindy, welcome to the podcast. Hello, Pam. I’m so happy to be here. It’s always fun to talk to you. It is always fun to have you on, and we’re going to talk today about like one of your favorite topics.

Aren’t we? Absolutely. I, it’s not my favorite topic. So tell me a little bit about how you got introduced to Beauty in the Word and Stratford Caldicot and this idea he has of remembering. Yeah, well, I guess it was at a Searchie conference that I must’ve heard Stratford Caldicot name bantered around, and I know if they entered around for a couple years in my mind before I actually settled down to read beauty in the word,

and I really didn’t know what I was expecting out of the book. It certainly wasn’t what I got. Definitely. I thought I was going to read something a little dry, a little confusing as you know, most educational treatises from scholarly men can be. And I, I guess the first section of the book absolutely changed my life and it was as if he took everything I intuitively knew and finally turned everything up,

you know, put the puzzle together and made everything fit properly. Especially when he started to talk about the Trivium. And he talked about what we called the grammar stage, really being what he called the remembrance stage or remembering. So that was huge for me at that time because it wasn’t that what he was saying was new. I mean, it was new,

but it was actually just like a piece of the puzzle I’d been missing. And it cleared up so much of why I was at odds with some forms of classical education where the Trivium was, the first stage of the Trivium was called the grammar stage. And, and many people took that to me. That means we cram as much in the head as possible,

as far as facts and lists and all these things. And rather than, and things the child knows nothing about rather than through stories and poems and wisdom and literature and music and singing, it was just a life giving way to look at the Trivium. Yeah. And, and this, this actually made a huge difference for me. And then he goes on.

So this chapter, the chapter that we’re specifically talking about is that the quote unquote grammar stage chapter in which he likens to remembering, and then he goes on and he does the same with the dialectic stage and the rhetoric stage as well. And, you know, talking about those in completely different ways than I had ever seen them talked about. So he goes through the entire trivium in the book and really kind of turns it on its head. But I think, you know, he calls dialectic knowing I’m actually flipping through my book right now. And then speaking is the rhetoric stage. And I like you, I was just really blown away by the idea that this idea of grammar is more than just facts, more than just thinking about facts. And my chapter is full of so many things that I’ve underlined. So talk to us a little bit about how this idea that Caldicot puts forth about remembering being distinct from, and yet still connected to some of the, the connotations that we might associate with memory such as recall or memorization.

Right? Well, it’s not like, so we had this idea of that. The Trivium is a grammar stage and there was a memory going on memorizing going on during that time previously, but it wasn’t a life giving memorization. It was really a kind of a disconnect. So Caldicot basically takes it back and says, this is what the grammar stage is for. It is for actually remembering beautiful thing. And those things are building the foundation. It’s still a foundational level, but the foundation, rather than being a pile of facts, it is that you’re memorizing is,

is so many beautiful things that you’re still kind of memorizing. You’re still memorizing these things. I’m a big fan of memorization. I, I think there are very few things it’s helpful. And, and at any age than memorization, even as older people, memorization still extremely helpful in our lives. So at every turn, I think memorization is a foundation of whatever ever we are doing.

I wouldn’t teach a child to sub almost every subject you could throw in some kind of memory thing and not just, Oh, we’re, we’re in biology. So we’re going to memorize this or let’s say chemistry, cause then it’s easier or anatomy, we’re going to memorize the bones that when you’re older, you’re doing those things, but they’re even beautiful things apart from that,

that you can memorize as a whole. And not, as in other words, it’s carrying blasts and say, we can memorize some aesthetically rather than analytically. Oh. And so like you’re talking and I’m thinking about the quote in the book where he talks about how well he’s talking about Plato. And he says that, you know, memory has been stripped from us.

And all we possess is an external reminder of what we have lost. And this was like this next little candid part. He said, enabling us to pretend to a wisdom and an inner life. We no longer possess in ourselves. And so he’s saying, if we don’t have this remembering, if we don’t have this memory, then we’re just kind of pretending to knowledge here.

Yeah. And I think that is very true. And I think that you see that going on a lot and you know, real education and real knowledge produce should produce in us a humility. So when we see education not doing that, or when we see a form of like say classical education or intellectual education, or even even a read the reading life that produces a kind of a know it all,

you know, arrogant or, you know, how can I want to view, you know, I’ve, I’ve read more than you have then that’s not at all what we’re looking for. We’re looking for what we’re looking for is going to humble us. And, and it’s going to be something that brings us life and not the death that we get when we’re actually,

I read today this morning, I was reading that devotional I have, and it’s by Tim Keller. But he says here in the prayer at the end of this January 8th day, Lord help me to avoid the world. The world shortcuts, the cynical air, the inside joke, the size and things, sadness about how stupid everyone is. Let me despise no one and respect everyone.

And I just thought that was a really appropriate for what, what w what education, how education can go wrong. So, okay. So we’re talking here about a deeper kind of learning. We’re talking about a remembering or recalling, and you speak about this and you write about anchoring and tethering our children to a cultural heritage. So I’m kind of moving now from what memory is to what things were supposed to be remembering.

And Callicott about memory and tradition as ways of passing down culture and joining generations together. So what kind of cultural heritage are we talking about? What did you work to pass down to your children through morning time? Are we talking about like, Go ahead. No, no, go ahead. You, do you ask, I’d like to hear what you were going to say.

Are we talking about like The Christian tradition, American heritage, Western civilization, all of the above or something else entirely All the above, both, both, all of those things. And also the poetic tradition, all of these things we’re going to bring to our memory, to the memory. I think most children should at all times have maybe three pieces of memory going at a time.

I don’t think that’s too hard. They don’t have to get through them in a six week period. They can take, you know, a half a year or a year to memorize if they had to, but I still think it does the brain good to have different types of memorization. So a child might be memorizing the first amendment and he might be memorizing,

you know, the first 10 verses a Genesis. And he might be memorizing a poem on top of all that. So I always thought it was important to have kind of a two-pronged memory. Well, the Bible poetry, and then something that was cultural tied into the culture, either the culture of the church, you could do a creed, you could do all kinds of things like that.

A prayer that you hear that sounds beautiful. We did the West, the West point cadets prayers, a beautiful prayer for boys. And, you know, that was just a cultural heritage because when you’re memorizing these things, you’re hearing them over and over and over again. And you’re also picking up things about the past. I like to say that the path has its DNA that is locked into some words,

these words, that we’re memorizing. So as we’re memorizing or even singing a folk song over and over and over again, suddenly there are words that we wouldn’t know that take online. There are cult whole cultures of people that become embedded in our soul that we understand in a new way that we might not even know that we know, and that will feed us the rest of our lives.

So I, I just don’t think there’s much that we do that bears as much fruit as that. So you’re saying that, you know, you have these three pieces of memory work going and it’s okay if they don’t get it quickly, it’s okay. If this takes a while for them to actually kind of master the piece. Yeah, absolutely. In some cases they’re going to master things easily and some kids are never going to master them.

They’re going to have worked on the piece for six weeks, eight weeks, 10 weeks, and still, you know, miss, miss a word here and there consistently. That’s okay. That’s okay. We don’t have to insist that we don’t have to ruin the experience for that child because he’s still getting all the benefits of having those words in his heart,

even if he doesn’t have them word. Perfect. Okay. And so at that point you would, you would give it a time and when they had it mostly good, you would move on to the next one because they’ve gotten the idea from that piece. Exactly. That’s what I would do. I would, I mean, I wouldn’t kill it because we’re not be laboring the peace.

We’re not over and over talking about it and make it just killing it. We’re just saying it each day quickly and going on, we’re moving on and letting it do its own work. I mean, and that’s how I feel it should be done. There are times when everybody at once, it’s like, Oh, what in the world does that mean?

And we can look it up. But for instance, when you’re doing to be, or not to be, you can go for months or weeks going, who was Farnell bear, who I forget the line, but who knows what that means? And, and no, you don’t have to look it up right away. You don’t have to be like,

Oh, let’s look this up. Sometimes it, you might want to do that. And sometimes you just might want to let that sit in the mind because that’s what the mind is going to work on. Looking for that, trying to figure that out, let the mind do the work, not the mom. Ooh. That’s a really, I’m going to copyright that.

I’m writing it down right now. So we don’t forget it. I love that so much because so long, Especially with like, you know, scripture and harder pieces of poetry and things like that. We want to, you know, provide the answer for our kids and tell them what it means and, you know, so I think that it’s okay to kind of let them too on that.

Now I do think it’s important to make sure they’re saying the right words. Yes. Because if you’ve Ever heard a kid like butcher prayers, they can get way left field with what they think you’re saying. That is true. You can have all kinds of weird theological mistakes going on when you get so totally miss out on what the point of the word is and kids will do that frequently.

So it’s, it’s hard to, it’s hard to correct them sometimes, but yeah, I think getting the words right is good. It’s a good thing. Definitely. Yeah, but they don’t necessarily it’s okay. If they don’t 100% understand everything that they’re saying, because that, that wisdom is going to come to them over time. Right now. They’re just,

they’re getting those there’s words internalize. Yeah. You know, thinking about that. I think about when I go to church, sometimes they’ll sing a hymn, an old him and somebody holds, decided to update the wording so that it, it makes more sense to modern audiences. And I just feel like that takes all the intellectual meat out of the, him,

that him was written a certain way by the author. And when we, when we don’t quite understand the wording, it makes it interesting to us because then we think about it and, and our minds work on it. And it, I just feel like it’s super sad when somebody thinks that to make the line simple will improve the him. That’s just my,

my opinion That, yeah, that’s interesting. That’s making me think of a, another situation that’s going on right now with the Lord’s prayer or the, our father apparently. And I, and I don’t know, like the whole deal, but you know, I’m Catholic. And so the Vatican has come out and said, Oh, what’s the line lead us,

not into temptation. So you’re asking God to lead us, not into temptation. And they’re saying that the, the wording on that one should have been different all these years and the, because God would never lead you into temptation. And so I’m just sitting here going, Oh, you know, this is going to take some pondering on my part as to whether or not I’m ever going to be able to say anything other than lead us,

not into temptation, which I know it’s kind of a different, a different thing, but it’s like, It’s true because we, it is like, there it is tiny. Like God doesn’t lead us into temptation. It says that clearly in the Bible and prayed that all this time did we, did we just intuitively understand what it meant. Right. Don’t worry about it too much.

Yeah. I’m still chewing on that one. I’m not quite sure. I’m not quite sure what my feelings are. Yeah. Yeah. They’re changing something or, you know, or clarifying something that has been, that I’ve said for all of these years. And, and I think I did know that, you know, it was never that God was going to lead me into temptation,

but so even though I haven’t been, yeah. So anyway, it’s interesting. Yeah. Really get messed up here if we started. Right, right, right. No cultural heritage. And you touched on this a little bit already, but what do you think our cultural heritage is made up? So if a mom’s listening to us and they’re like, okay,

well, I kind of liked this idea of using memory to pass on cultural heritage to my kids. And we talked about Christian tradition and American heritage in Western civilization, but can we get more specific? What are some things that bind us together? And, you know, I know scripture is definitely going to be one, but what else? Well, I mean,

we set the creeds, you know, the th the apostles creed, I think, what is it, the nice thing, creed, the creed that we all can agree. Nice. I mean, the Catholics do both. We do the apostles and the nice scene, but I think the nice scene is the one that is said and like more traditions.

Right, right. And there are some things, there are some great memory, memory, things from American history. There are there’s Thomas Paine. These are the times that try and unfold. And when you start reading, especially when you go back in early American history and you start reading the, the, the declaration of independence, maybe the first part of it,

or the preamble to the constitution, and you see the sentence structure and you realize how highly intellectual these men were. And th their, their facility with language was incredible. And it just makes us better people to know that we’re a little dumbed down, but you know, that this was, this was a different way of speaking and writing and it, and it was very precise and,

and it helps us. It helps our children, I think, to see, and to know, and it creates that humility once again, that, Oh, you know, I’m not the end all with my little, you know, little things. I do. I, there are people that came before me that, that had incredible abilities and it,

by contemplating what they wrote, it can become a part of me and that can have consequences. Yeah. Yeah. Well, that makes me think of the part in the chapter where Caldicot talks about, and he kind of likens this to a speed. You know, we don’t need to remember anything because we can Google things, but back in, and I think it was Plato who was the one who was complaining about the fact that people were writing things down.

Right. And he was worried that by writing things down. Yeah. Plato’s critique of writing calls into question, the whole myth of progress that shapes our view of human history. Caldicot just gives us those little zingers, but he was talking about relying on external marks on paper to call things to mind that will lose their capacity to recall things from within themselves.

Right. So, right. We are like saying, Oh, you know, now we don’t even have to remember anything. We can just Google it. But even farther back, you know, Plato was saying, Hey, you’re writing things down now. And you’re going to lose something by doing that because we’re not, we’re not internalizing this stuff and remembering it inside of us.

No, I think because we have Google, it’s more important than ever for us to memorize, not back because we do have Google, but these other things, these other ways of speaking and looking at the world, the Western tradition, our heritage, and even sometimes looking at other cultures and other heritages and seeing the way that they looked at the world and the way they interacted with it.

And yes, you’re right. I think, why do you change things? And, you know, they even say, I heard a pastor say he didn’t, he didn’t allow them to record his preaching because he said, just the act of recording, it changed. It changed it. So there’s, there is, there is a lot there and we can’t,

we can’t go back. We can’t, you know, we do write and writing is a great way to think, but it is also a great way, way to forget. And if the goal is remembrance, which is what Stratford is saying, it is, am I, I fully believe you are correct then to do the things that cause us to remember.

It’s very important, especially for our future, for the future. Not just now we have to hold on to the past as we go into the future and we are going to go into the future. We’re not saying we’re gonna, you know, dress up in hoop skirts, you know, and pretend to live in another time. And I think homeschoolers have made that mistake before thinking,

well, we’ll just live in a different time. No, we’re not able to live in a different time, but because we are going into the future, we must carry with us the wisdom that has come from the past, because that’s the only way we can get with them. We’re not going to get it within ourselves if we don’t look back. Well,

speaking of her hoop skirts, and we’re talking about cultural heritage here, how do you handle aspects of our heritage that are not positive? Yeah, that, that’s a very good question. And there are times when, well, I’ll tell you how I handled it this year. This year, I read two books to my students that had portrayals of racial portrayals that were awkward.

One was huckleberry Finn, and they used a word that I don’t use in that book. And the other was roll of thunder. Hear my cry, which also used that word, that same word in a different way, in a more and huckleberry Finn. I, I believe Mark Twain purpose in writing that were pure and good towards African-Americans. I, but he wasn’t an African-American.

And so I just changed the word. And when I was reading it aloud, I’m not saying that a child couldn’t read that word and understand the context. I would definitely have a conversation about it. I would not hand a child huckleberry Finn with the conversation, but I enroll a thunder, hear my cry to take out that word would be taken nine,

the pain and suffering that the family had faced. So we just kept the word in and we talked about this. This is how bad it was. This is how, this is why this family. Now, this is what they went through and look at what great attitudes they have and this sort of thing. But there are other books that, that definitely come from a much,

much more, less innocent aspect of that, of a different period of time. You can’t change people in the past and you can’t make them over. And to what we think is right today and what, you know, the values that we’ve had the luxury to have in our culture, some of the values that we have our improvements and we are doing better.

And we do think more highly of one another, not, not basing it on, you know, our sex or our race, but that does not erase the fact that those people in the past also had wisdom that we may have forgotten. And so I try to be just, I don’t, I don’t want to, we don’t have to whitewash what they said.

We don’t have to, we don’t have to say, Oh, this is good because they said it, but we can say, well, they have some good things to say, but they also, in their time, this was considered good. There were times when Christians, when, when evolution first came out, many, many Christians thought, well,

it’s a done deal. They didn’t know there was so many Christians became evolutionists, even though they still Clint were still Christians. And we just have to, we can’t say, well, I’m never going to read that person because it looks like they liked evolution. We have to be broader minded than that. We have to see that they only had a certain set of information and we only,

we have a different set and we, if we’re going to, and we can learn from them because if we limit ourselves to just books that are written in our time with our values, we are going to be severely crippled as we go into the future. In my opinion. What do you think? I mean, you might have a different opinion,

so I’d love to hear that if you have it Making me think. And so I have to kind of process the information. It doesn’t come out that quickly, but, you know, I, I think you’re right, because you have to know the whole story. And so you can limit yourself to one small piece of the story, just because it’s the piece that you agree with.

You have to know the entire story in order to, you know, make judgements and be part of the conversation. And, and so you just can’t leave parts of it out. And so just because you read something or, or just because you experienced something doesn’t mean that you necessarily agree with everything about it. Right. I do think it’s important to look at things from all sides in order to,

you know, come up with your own thoughts about something. Yeah. And we don’t, I mean, there’s very few things that we’re going to agree with anyway, unequivocally even now, I mean, things that are written now are not necessarily better for being pure. You know, there is a point of no return where we purified the truth right. Out of things.

And that’s a sad moment in time, too. Yeah. Yeah. That’s interesting. Well, as you’re looking back on morning time and doing this for all of the years with your kids, what, what kinds of things that you did? What things do you think conveyed cultural heritage to your children? And I know there’s just memorizing, but what else?

Well, I mean, we read aloud a lot of historical books and when we first started, I didn’t know the history. So I’m reading these very basic, maybe first and second grade book out loud to my kids. And I’m like, wow, I didn’t know that. And I think it was the time that we had to devote to those things.

So we got a, we got a really broad picture of the heritage that we came from, especially we were very good at doing American history early on. And it wasn’t until later years that we got into a lot of the ancient history at the very end of my homeschooling career. I finally read the Iliad and the Odyssey out loud to two of my children.

And I, I, it w it was, it went very well with the American history that we had read. In fact, in that is also Plutarch. If you look at Plutarch’s very much tuned in, I mean, you will not read anything and it doesn’t sound contemporary. Well, you might, there might be some weird things about sandals and stuff,

but, but Plutarch is very relevant to our time. And you cannot read Plutarch without being aware that these were lessons that they learned and Roman and Greek times, and these, and these are so not so different from what we’re facing today. In many ways, they have the same problems with their leaders that we have with ours and seeing how they dealt with it can help us to,

because sometimes when you’re in a bubble, you think, Oh, this is the answer when really it isn’t. And then sometimes you can look back in history and say, Oh yeah, they thought that too, but it didn’t turn out to be that way. That’s interesting. And yeah, it’s good to point out. And we, we have a podcast where Ann White comes on and talks to us about Plutarch and how to study Plutarch.

And I think you’ve done an episode with her too. And it, one of the things that was fascinating to me was Plutarch was not history for Charlotte Mason students. It was actually like civics. Right. That’s right. It was citizenship. That’s exactly right. Yeah. So Plutarch that’s, that’s a good one. And then you mentioned hymns and folk songs and Right.

Yeah. I mean, we did story. We did a lot of, I can very PLLs I know you’ve had Angelina on fairytales are wonderful, different folktales. I love to go into the library section because it’s hard to cover all the folktales that there are out in the world. But if you just go into that section of the library and you start looking at the books and looking through those I,

that was always my favorite section of the library. There’s so many good books and stories and, and the, in the traditional tales section of even the picture book, there’s some wonderful picture books. And, and don’t ask me me, I’m trying to think my brain is, but they’re all like called out. He wrote some really good the, the,

the, the Peter shams wrote, these are some of these are really old books. And I know many libraries have gotten rid of some of these traditional, beautifully illustrated stories. Shakespeare is something else that the more I grow, you know, I’m still growing up in Shakespeare, but you can’t help. But, you know, Shakespeare is so cliche because he has affected our language in a real way.

I think it’s good to point out that, you know, just to kind of reiterate, we were talking about memorizing here, but we’re also, this remembering goes even deeper than memorizing it. It’s kind of this remembering who you are and your place in this, this grand story, this grand cultural story through stories, songs, poems. So it’s not just memorizing,

but it’s also listening to those stories and hearing those songs and, and all of those things, not just the memorization And just having, you know, beautiful music, classical music playing in the background is still important because no, your children might not grow up to be able to say, Oh, that’s the, you know, the ninth symphony or, or whatever,

but they will have an appreciation for it because there’s something about that music that speaks to our heart. And they will remember that it is good. And very few people actually hate classical music. I mean, at least if they’ve listened to it at all, they don’t, It talks about the connection between language and memory and how language helps us form relationships with ideas and helps us put the pieces together and figure out the world.

So how does this tie in with Charlotte Mason’s writings about ideas, relationships, and spreading the feast for our children. Okay. What is, what did you say? Caldicot said again, let me, let me get this clear in my head. It talks about the connection between language and memory and how language helps us form relationships with ideas and put together the pieces and figure out the world.

Hold on, let me see if I could find, Well, I agree with you that I agree. I agree with him. There is nothing. I think that is what the grammar stays. It’s language. I think that when we understand the point of the grammar spaces language, then that’s where this whole idea of remembrance comes in. And the whole idea of culture comes in.

It is very, very important to have a strong foundation in language and speaking, and writing and in it, and the grammar stage, you know, you’re not doing a lot of writing, writing the child was not writing things down, but he is, he is remembering because you’re asking him to remember what he is read. And that’s a deep part of an even before you’re him,

him that you’re reading them, you’re reading your children’s stories that they do remember. And they do want to remember. And then the child turns around and takes, it, takes all that. And if you give them time to play, then you will see the narration. You don’t even have to have a formal marriage. And if a child is able to play at a young age,

when they’re in this remembrance day, you’ll see this language coming out and in their play. I remember my boys used to say, you know, I’d hear them outside yelling, what’s over yonder. And then somebody say, I need the blunderbuss. And, you know, they’d be using all these really strange words. And I think, man, they’re really weird kids,

but that’s what they did with the story. They, they, they acted them out on their own after they had heard them. So, so Charlotte Mason is basically saying, you know, if you, if you are hearing these things and you’re, and you’re listening with attention and, and because most of these things are pretty awesome. People do want to listen with attention.

Then you are going to recreate them in some way in your life, as you think about them, as you, as you ponder them. And as you eventually, you know, you’re going to narrate them, but that’s just a natural process. So we want those early years to be language heavy language rich, really the whole point of the early years is to have the child interacting with words and ideas.

Yeah. There’s a quote at the end of the chapter that I just love, he says, and it’s like, okay, can I please go back and do this over again? Yeah. I can do the early years over again. Now that I’ve read this, but he says, the first lesson of our revised Trivium is therefore the vital importance of crafts,

drama, and dance, poetry, and storytelling as a foundation for independent and critical thought through doing and making through pollicis, the house of the soul is built. Yes. And then he goes on in that same quote, which is just really, really the heart and soul of everything he’s saying. And he brings out the point that poetry, and I’m sorry,

I didn’t already say this because it’s made of images, similes, metaphors, and analogies. And that is how language changes us. And that is how language works upon us. When we compare, you know, our feelings to something we see outside that that is a higher order of thinking and a child picks up that up effortlessly in this sort of education.

So, you know, you know, they say, what is it? The Miller analogy test is the highest test for intelligence that you, that, that they have analogies are not that hard for children who have grown up with poetry, constantly seeing language use in this way. Sure. They may not understand every metaphor, every analogy, every similarly that they come across in poetry,

but they’re seeing language use that way. And they are, it makes you have a heightened awareness that I get to pay attention. And when you get older and, and they, you know, they throw an analogy test in front of you, which they don’t do very much anymore because obviously people can’t handle it in the past. They did it. It’s not that hard to do analogies when you have been looking at the world through that as a metaphor through language.

Yeah. Yeah. And to, and then just to think about, you know, going back to scripture, I mean, it’s just, it’s chock-full of those kinds of things. So just to get pros things, we re everything, these analogies are everywhere. And so the poetry is the kind of training ground for understanding so many other things that are out there.

It’s like the mental exercise part. I always, I always say that poetry for me as the bridge between the Trivium and the quadrivium, the Trivium is language. If you wanted to choose to some broad words, say the Trivium is about language. And the quadrivium is about mathematics. Poetry is the bridge and music. Of course, music is very much a part of the quadrivium and it is mathematical in many ways,

but it is the bridge between those two things between music and language. So poetry is a very important part of heart. Very few things besides Bible are as important as poetry because of the higher order thinking and the delightful way it causes us to wonder also, and it leaves our brains. Just thinking, thinking, thinking what, you know, that’s why we don’t always want to tell the child what the poem means.

Sometimes we can, sometimes we can help them through so that they, the next home they get to, they can do the work on their own. You know, you go to bed at night. And I remember doing the reason I know this works is because there were a couple of homes I memorize over the years with the kids, for instance, and there were long,

long poems. One time we did Horatio to set the bridge, which takes a full 20 minutes. Well, we didn’t study that poem so much as we just said it over and over, but the more, the more I went and the longer I memorized that poem, the more sentences made sense to me as I went, you know, my brain couldn’t take it all in at once,

but eventually, Oh yeah, yeah. That’s, that’s a type, that’s a place, you know, maybe I didn’t even know it was a place when I’m tripping over all the weird words that I don’t normally see, but eventually my brain, you know, is able to say, okay, now I know that word means now I know what this word means.

It’s constantly working on it. So each day when I read the poem, it made more sense to me. Well, and I think, I think that brings up a very important point. Is that it’s okay if we don’t get it the first time, it’s okay. If we don’t understand it the first time, it’s okay. If we can explain it to them,

maybe we shouldn’t even be trying. We just need to let it. Yes, absolutely. Sometimes moms can get so excited about what they get, that they can kind of feel it from. I just read something CS Lewis said, I’m trying to think of where I read that, Oh, his letters to children, where he essentially said, I don’t know if I can find it right now.

But he Lewis said something really. I didn’t underline it because I was lazy. But a little girl asked him something about a poem and he’s just said something really, really. So what not, what you think he’d say, but rather what kind of along the lines of what we’re saying right here to her, and I can’t find it. So if I had underlined it,

I would have been able to find it, but I did not. I understand. Well, let’s talk about Caldicot describes the haul of fire in Rivendale from Tolkien’s Lord of the rings trilogy as the place where tradition is passed on through story where meaning is revealed, where language expresses itself and the making and interpretation of, of worlds. How can morning time become our ribbon Dale or our place of hospitality and rest a place of story,

poetry and songs. Okay. Wow. I mean, when we’re building a family culture, when, when we’re doing stuff together, we’re building a family culture and I think that’s extremely important. It is that whole, because you do share those things, they never can be taken away from you. When I talked to my children, you know, now,

and I say something that we haven’t, we have a common culture and a heritage that, and, and you even see this breaking apart in our culture. Now it used to be, we, we would read books together. We would read poems together. Or, you know, of course, morning time does that, but in the culture, but then like TD radio came along,

but still people were sitting around the radio together and listening to stories. But then later TV came along, but still people were sitting around the TV that, you know, everybody had their own TV, one TV in their home, but now nobody comes home on Monday night and watch this little house on the Prairie all together. Like we used to do when I was first married,

Monday night was my little house on the Prairie night. My husband would come home from work and I would be sitting there. He would get home about eight or right when the show was over. And I would just be sitting there sobbing every week after the end of the shift, because it was just so melodramatic and said, but there was a shared culture where everybody in the culture would say,

Oh, did you see the little house on the Prairie last? And they now we’ve lost that so much because we all can stream and watch something on our own. Now we may find a tribe of people online that they’re all watching this show together, but it’s in our family, you know, we’re all watching something else. And so we don’t have that conversation.

We don’t have that. We don’t have that fire that ho that great hall with a fire transfer culture. We’re, we’re, it’s becoming more and more and more fragmented. Every everything that we do, all our stories are far, far apart from one another. And we don’t have a common, a common culture to share them with. I mean, when you think about,

I don’t know how many stories the Greeks actually had, we know that they had the Elliot and the Odyssey, and maybe, maybe they have hundreds of stories or maybe they only had a few, I don’t know. But every, because that was their only entertainment. They all knew those same stories. Yeah. That’s that one will make you think that is an interesting thought that they all knew the same stories.

And so that it was something that, that bound them together. And even in the Bible, you hear Paul talking about stories that he assumed everybody knew, and we don’t know them now as much, but he’s speaking about stories and things that, that they were familiar with at that time. I’m going to have to chew on that one for while. Yeah.

It’s like, Oh man, that’s really good. I mean, we, you know, I’ve talked about shared family culture before and about, you know, being able to, to kind of have that idea of, Oh, so-and-so knows, you know, we, we all know the same things, but I think it was like this moment that it struck me absolutely how important this was,

that, that our shared family culture and everybody knowing the stories is kind of a reflection of, you know, this, this greater, like the Greeks and everybody knew those stories. And so that’s a cultural heritage that is lasted for so long and had such a huge impact. And was it because everyone knew the stories. Whereas if you look at us where we are so fragmented and we don’t have stories that everyone knows anymore,

you know, a thousand years from now, what impact will our, Yeah. Yeah. I mean, it really is something to think about and to think, is there something we’ve replaced stories with? Is this something are, or is it just that we’re gorging ourselves on stories? And we just have so many stories that they can’t have any effect on us because we’re,

or the effects they have is, is not culturally as a group, but it is too fragmented too far out. I like to talk about that whole thing of being heathered like you say, and I got that idea when I was watching one of those weird movies in space where the guy got lost. He was unhooked from, he was tethered to the space thing and it was George Clooney.

Everybody will know this movie, but my brain won’t come up with it, but he was tethered to the spaceship and he got untethered. And then he was just lost in the universe. And it was just so profound watching it. It was also terrifying to think of a fairy was he’s going to live the more, I mean, he wasn’t gonna live very long,

but he was going to live completely disconnected from everything. And I started thinking about what, how does that affect us? Is that our job to tether put as many tethers into our, our ourselves and our children. Because honestly, sometimes we don’t have, even with our children, we don’t have complete autonomy over them. Eventually this is coming from a mom has learned that the hard way,

but, but we do even ourselves, even for ourselves, it’s important that we’re tethered to the past so that we can move into the future because otherwise it’s just insanity. And I think we are seeing a little bit of that now, as everything is untethered, you can say, you know, we have this center, but all these stories are just flown out and they’re just all over the place.

And they’re just like rock in the air. Like the universe, my metaphors are going to get weirder and weirder. Yeah. I’m going to entitle this podcast. Deep thoughts with Cindy Rollins. No, but just thinking about, yeah, No, but this, you know, this is kind of our role to tether our children and that we are, I mean,

there is a lot of, there is a lot of untetheredness or a lot of fragmented, you know, fragmented newness and yeah. And, and I think that just, that just brings me back to the quote from earlier and now I’ll have a hard time finding it, but Plato’s critique of writing calls into question, the whole myth of progress that shapes our view of human history.

We think we’re so, You know, we’ve progressed so far over these old cultures, but maybe honestly, we haven’t, you know, when people say to me, do I have to have morning time? Which I always find to be a really odd question. No, you don’t have to have morning time. And you said your choice altogether. But when I think about these things,

I think one time, if you want to preserve culture, this is, this is a really simple way to do it. No, you don’t have to have, there are other things you can do in your family that can preserve your culture. But if your children are all just off doing all their, all their schoolwork all by themselves, each in their own way,

and you’re doing your own thing on the computer or whatever, there are times for that. And that’s good. But if that’s all that you’re getting out of homeschooling, then, then you are missing a huge philosophical gap there. And, and that’s why, you know, reading aloud is a start. I mean, even if you can’t pull off a morning time,

you can pull a, hopefully you’re pulling off reading the loud one, one, or, you know, one book to your family at a time. And that, that is another form of doing that. Well, we’re gonna end on that note. I think that’s a fabulous apologetic for morning time, and we’re just gonna, we’re just going to let that hang out there and let people think about that one.

So thank you so much for joining me here today. You’ve given me a lot to chew on and it’ll be, it’ll be a few days before I impact all of this one in my head and think about it all. Tell everybody where they can find you online. Okay. Well, you can find me@cindyrollins.net. That’s my new home online and on Facebook as Cindy Rollins,

a writer speaker encouraged, or I’m not sure how you find that on Facebook, but if you want to like those things, that’d be great or sign up for my new newsletter. That would be fantastic. I’m I’m hopefully still tethered, but I’m moving out into a new, a new adventure to see where I will have. So that’s where you can find me.

And there you have it. Now, if you would like links to any of the books and resources that Cindy and I chatted about on today’s episode of the podcast, you can find them on the show notes for this episode. Those are@pambarnhill.com slash Y M B 65. Also on the show notes, we have some helpful instructions for you. If you would like to leave a rating or review for the,

your morning basket podcast in iTunes, the ratings and reviews that you leave, help us get the word out about the podcast, a new listeners. And so we really appreciate it when you take the time to do that. Thank you very much. I’ll be back again a couple of weeks with another great morning time interview. We have Alicia great house and her daughter,

Olivia, they’re going to be on the podcast with us, and they’re going to be talking all about their brand new podcast, masterpiece makers. Now this is an art appreciation podcast for families. So moms can listen. Kids can listen, everyone can listen together, and it is just so much fun. So we’re going to be talking a little bit about art appreciation about this new podcast and about how you can use it in your morning time to add a little art appreciation to your day.

So we hope you join us for that. And until Ben keeps seeking truth, goodness and beauty,

Links and Resources from Today’s Show

- SPONSOR: A Month of Morning Time

- Cindy’s Website

- Mere Motherhood

- Mere Motherhood Facebook Group

- Mere Motherhood: Morning Times, Nursery Rhymes, and My Journey Toward Sanctification

- A Handbook to Morning Time

- Beauty in the Word: Rethinking the Foundations of Education

- Declaration of Independence

- Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

- Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry

- YMB #13 Plutarch 101: A Conversation with Anne White

- YMB #41 Why Fairy Tales are Not Optional: A Conversation with Angelina Stanford

- C. S. Lewis’ Letters to Children

- The Hobbit and the Lord of the Rings Trilogy

- Little House on the Prairie: The Complete Series

- The Great Homeschool Conventions

Key Ideas about Remembrance

Find What you Want to Hear

Pin

PinLeave a Rating or Review

Doing so helps me get the word out about the podcast. iTunes bases their search results on positive ratings, so it really is a blessing — and it’s easy!

- Click on this link to go to the podcast main page.

- Click on Listen on Apple Podcasts under the podcast name.

- Once your iTunes has launched and you are on the podcast page, click on Ratings and Review under the podcast name. There you can leave either or both!