Pin

Pin

Join me today for a delightful conversation with a Charlotte Mason homeschooling mom who also is a poet. In this episode, Sally Thomas and I discuss what drew her to writing poetry. how to experience poetry with your kids, and how you might encourage them to write their own.

Pam: People are intimidated by poetry because they think they have to do a lot to make it happen. And the truth is you don’t, you don’t have to do any more to make poetry happen in your home than you do to make stories happen in your home.

This is your morning basket, where we help you bring truth, goodness, and beauty to your homeschool day.

Hi everyone. And welcome to episode 93 of the, Your Morning Basket podcasts. I’m Pam Barnhill, your host, and I am so happy that you’re joining me here today. Well, on today’s episode of the podcast, I am joined by homeschooling mom and poet, Sally Thomas. Now I very quickly discovered as I was talking to Sally, that I probably could have any number of fascinating conversations with her, for the podcast, but it just so happens today we’re talking about poetry, but man, there is a wealth of homeschooling information there. And so she mxkes for an absolutely fascinating guest. But today we are talking about reading poetry in your homeschool and also, you know, having your kids try their hand at writing a little bit of poetry as well.

And what makes a poet and why does somebody want to follow that path. So much fun! I think you’ll be inspired by the conversation and speaking of poetry, it is one of our very favorite things in your morning basket Plus. Your morning basket plus is where we have ready made morning time plans and monthly theme Explorations for you. We’ve done all the work for you to help you plan your morning time and every single set of plans and every single Exploration includes poetry that we’ve chosen.

So if you’re still a little intimidated about picking poems, we have some really great ones that we’ve chosen for you and put into every set of plans. And we also memorize a poem together each month with a memory palace. Now, if you are interested in finding out more information about your morning basket plus and becoming a member, you can find that at Pambarnhill.com/YMBplus And now on with the podcast.

Sally Thomas is an accomplished poet and fiction writer, wife and home educating mother of two graduates and two seniors. She holds a bachelor’s degree from Vanderbilt University and has pursued graduate coursework in English and creative writing at the University of Memphis and the university of Utah, her writing has in various publications, including the New Yorker, first things, lay, witness verily, and the Catholic literary journal dappled Things, just to name a few. She is the author of two poetry, Chatbooks fallen water, and Richele dis of Walsey numb and has a full length poetry book called Motherland, which was a finalist for the able muse book award. And it’s available from Abel muse press and anywhere books are sold.

You can also find Sally at her blog Abandoned, hopefully homeschooling.com, where she writes about homeschooling in the Charlotte Mason philosophy. Sally, welcome to the podcast.

Thanks Pam. Great to be here.

I’m so glad you’re here. Well, let’s start by talking a little bit about you and your family and maybe a little bit about what your homeschool Was like.

Okay. Well, as everybody now knows from the introduction, my husband, Ron and I have four kids, we have a daughter who’s 27, a son who’s 23, a son who’s 18 and a daughter who’s 17. So currently the 18 and 17 year olds, they’re not twins, but through the magic of homeschooling, they’re in the same grade and they’ll graduate this year and that’ll be it. Wow. So, I mean, when you say what my homeschool was like, and a lot of ways I really am looking in the rear view mirror. And what it’s like now is not very much like what it was like when I started out with four kids.

We started homeschooling when my oldest was nine after she had been in school for four years. So I had nine five one. And at that time unborn, my number four was born in December of our first year of homeschooling because it wasn’t an interesting enough year.

I was going to say, that’s a lot of change in one year.

Yeah. We had made a Atlantic move and you know, done this kind of free fall back to our home town. So we were all in shock. And then we had this new baby who was wonderful. She’s a wonderful baby. She’s a wonderful 17 year old, but it was a crazy year. And so really our first two years of homeschooling, I tell people this all the time, people tell you to D-school when your kids have been in school. And we basically did that for two years.

We took kind of a two year unschooling sabbatical, which was a really rich time, like a lot of learning went on in those two years, we did a lot of reading aloud. We did a lot of field trips. We did, you know, anything. I could just put a baby in a carrier and, you know, somehow restrain this manic toddler and you know, my kindergartener and my fourth grader, you know, we would just, we would just kind of go. And, and so we did a lot of life learning and you know, just a very unschooly orientation, but philosophically I really, there are a lot of places where I get off the bus with unschooling as it’s kind of properly understood and which I don’t necessarily want to go into all of that right now.

But the Charlotte Mason philosophy, which I’d read a lot about in the year before we started homeschooling, I’d been, we had started thinking about it. Cause my daughter’s school experience was just, just doing a nosedive and we knew we had to do something different. And so I, you know, we knew a couple of families in England who homeschooled and that’s what started me thinking that I might try this.

And so I, I spent this year researching and the Charlotte Mason philosophy just struck me as the most humane and literate and soul sustaining kind of education that could possibly exist. And I knew that was the direction that I, that I wanted to move. So about the time my oldest daughter was turning 11, everybody had turned over a couple of grade levels or years, and we started to implement the Meter Amabilis Catholic Charlotte Mason curriculum, which we’ve really used all the way through since, since that time. I mean, I’ve modified it for our own purposes every year, but that’s kind of been like the backbone of what we’ve done. And I, you know, I started with sort of, you know, an 11 year old and a seven year old reading out loud to them while toddlers were just doing chaos all around us.

I don’t even remember what the toddlers were doing, but they’re still alive. So I guess it was okay.

So you can block that out eventually.

It’s amazing what you can forget. It’s like childbirth, you forget. I guarantee you like your first year of homeschooling, you’ll remember these wonderful moments, you know, family coziness, and you will forget like all the crying that you did and you know, all of the chaos. And so we just, we just, I dunno, I mean, we, our homeschool just kind of evolved organically over the years.

You know, we had this real steps in stairs of ages and stages that, that I sort of had to accommodate, you know, from like keeping the toddlers from killing themselves, to helping the early elementary child really get launched in reading and math, to by the time we really started doing formal school after this two year sabbatical, I had a middle schooler and, you know, to sort of start to align this child. I mean, it’s kind of, it’s sort of shocking to your system to think that you have an 11 year old and you, you really should be thinking three moves ahead about where they’re going to be in a few years when they’re ready for high school, but you do kind of start thinking that way. So yeah, you know, a real, a real spectrum of people’s needs and ability levels in, in the beginning. But all of that seems like ancient history now. I mean, my last graduate was in 2015. And so I’ve had these two who are basically they’re 17 months apart are basically the same age who have been doing basically the same thing for a lot of years.

And I mean, I also kind of feel like I’ve been doing high school continuously, forever. Yeah. I mean, my oldest daughter graduated in 2011 and that was about the time my next one was starting high school work. And I guess I had a little gap because my, my last two really there, their high schools sort of started around 2017.

But yeah, I just feel like I’ve been doing this forever and what our homeschool looks like these days is, you know, them doing some work for me, usually kind of on the fly, cause they’re not home very much. So like I use a blog to keep them, like I post their work with links and links to Google docs where they write narrations.

I mean, our whole foundation has always been read and narrate, you know, the foundation of the Charlotte Mason method. And so I guess we’re kind of techie just because I have to be able to do this remotely. So, you know, I have their weeks worth of assignments up on a blog. They have a Google doc where they write narrations.

So they’re doing some things for me. And then they’re taking right now, both of mine are taking two classes each at Belmont Abbey college where my husband teaches and as dual enrollment students. So our, our high school tends to be kind of hybrid that way. And we’ve always done that ever since my first child was, was in ninth grade or 10th grade actually is when we moved here, my husband started this job. So that’s just kind of been our MO for this stage. And so our homeschool really looks a lot like older teenagers who are very much on the go. I mean, they drive themselves to and from campus. My daughter has a job as well. They both kind of have their circles of friends and activities.

And even with COVID, you know, they’ve managed to be pretty busy all the time. And so, you know, I mean, they’re very independent with their, with their reading and writing and I catch up with them via their Google docs and write back to them and catch up with them when we’re in the kitchen and say, you know, that book I assigned on Monday is still sitting on the shelf in the hall, either explain to me why that is or make that change so that you don’t have to explain. So, I mean, that’s what we kind of look like these days. Wow. And you know, so lots of changes.

It’s amazing. Like just the, the distance that you’ve come. And I love the fact that you’re like when we started circumstances dictated that, you know, so many people worry about making that transition from school to homeschool and they err on the side of, I’ve got to make it look just like school and, you know, to being thrown into that situation, with that, you know, international move a one-year-old, which I’m sorry, a one-year-old is way harder on homeschooling than a newborn is.

Oh, I know, I know. Yeah. You can’t just hold the one year old all the time. No. And this one was, I mean, he had been walking since he was nine months old. He could, I mean, we still laugh about this, that he was the kind of little child who could walk into a room and something would spontaneously break.

I mean, it was, and we were living in an apartment, so it was just like insane all of this energy contained in this very small space. So it’s like.

Yeah, like you, you stepped out in faith and you, you, you did what, you know, you brought her home because you knew that was the thing for her.

Yes, yes. Here’s what you could do. And probably created this, you know, if you were to go back and write a book about those days, this wonderful lifestyle of learning that had weighed, you know, had a lot of value in it, even though it didn’t look formal. And then you were able to make that a more formal transition as it met your need.

Exactly. It was the difference between having to fight people every day to do something that they didn’t want to do because they were just still too close to the school experience. And even though it hadn’t been very happy, it was like, well, this is not school and you’re not a teacher and there’s no way I’m buying this.

You know, two years later after just reading together, learning together, living together, kind of reconnecting and our relationships, we could do this without a fight. And it was so much better. It was just, you know, I have zero regrets and nobody was behind. I mean, that child who supposedly lost two years of her education still graduated from my homeschool at 17 and went to college where she graduated with honors. So nobody, nobody was behind, you know, this wasn’t to anybody’s detriment. And it’s a lot easier to see that with hindsight, but that’s always how I want to encourage new people who are just anxious because you know, this whole elaborate school plan that they have is not working. Just let it go.

Yeah. It couldn’t be that back. And letting things go is the best thing you can do for them.

Right. That’s not the starting point. So anyway, that’s, that’s kind of our homeschool trajectory.

Well, I love it. And I, what I’m seeing now is, you know, you did, you spent all of those years in the trenches with all four of those kids, and now you’re living a very different where, you know, your role is very much facilitator of just a couple of classes. And so did there come a point, cause we’re going to shift now to talking about the poetry and everything and your authorship of it. But did there come a point where you’re like, was it always a thing or did there come a point where it’s like, well, I’m just not needed as much and one day I’m going to have this empty nest and I’m going to look for something to do with myself.

Well, I mean, the pendulum has certainly been swinging. I mean, I’ve, I’ve always been a writer and just compulsively from the time. I mean, before I could read and write, I used to tell myself stories. I mean, my mother just thought I was a very weird kid. Other people’s children didn’t do this in her experience, but, you know, I would just take like a puzzle piece and go off in a corner and tell myself a story with it.

When I could write fluently, you know, I can remember being, and I was, I was really kind of poor student in school because I just, I just didn’t like school. And I don’t know, you know, I mean, possibly I, I mean, I have a lot of sort of like attention deficit tendencies. I don’t have diagnosis, but clusters of lifelong behaviors really kind of point in that direction. I was kind of one of those smart, but scattered kids who’s just zoned out somewhere else a lot of the time. And, you know, I mean, I came really close to flunking fourth grade math, I mean, I came close to flunking math every single year that I took math all the way through school. Cause I was writing stories in class as well. I mean, I like had this ongoing saga of horse stories that I would just write in what was supposed to be my math composition book. And you know, so this was like a bone of contention at home, but here I am. So I had always been a writer and, you know, and people do talk about like writing and other arts as a vocation.

Right. You know, like, you know, that you’re called to do things. And I mean, I think for women, especially because of our, you know, if we’re called to marriage and subsequently motherhood, I mean, that’s sort of like an official vocation, you know, but we are because of our position in that vocation, you know, if we have these other callings like to, you know, an art form, that’s very demanding, you know, we spend a lot of our lives kind of negotiating that and, and figuring out what the balances are going to be so that we’re not just completely losing touch with that. You know, very central part of ourselves. That is, that is that calling to an art form.

But at the same time that we’re not like shoving our families aside because that’s our vocation too. And I, you know, I, for myself, I certainly didn’t want to be like, you know, someday that the, you know, very artistic mother of extremely bitter adults, I, that was not the scenario I wanted. You know, I very much wanted to be a, a good and present mother to my kids. And especially when we took on this home education thing, which as I told you before I, you know, was not what I started out to do. And it’s what I did end up doing. And it’s just been another, you know, another thing to balance in the mix in much the way that like an outside job would be.

I think I, you know, like, I don’t think homeschooling is uniquely problematic for a mother who also writes or paints or is a musician or whatever, but it’s just another one of those pieces of your life that you have to balance. And I guess poetry is good because you can do it in really small increments. You know, most poems are pretty small and you can feel like you’ve gotten something done.

If you’ve written a line or get, you know, you put a semi-colon in and you took it out again. And you’re like, Oh yeah, progress. Yeah. Yeah. Right. So I, you know, I mean, it’s like, you can, you can keep your, your connection going, but certainly as my kids have gotten older and more and more independent, the pendulum has swung back toward being able to write more. And I, I really, I mean, I’ve started writing fiction a lot more particularly because prose is just bigger and it does take more time to do. And so I have been doing more of that and, and just things like book reviewing and other sort of like literary critical things. Stuff I went to graduate school to do, and haven’t done in years and it’s really exciting to rediscover it and you know, that I like it, but definitely things have shifted with the seasons.

One of the things I love about what you just said to me, and I don’t even know if you’re aware that you said it, maybe you are, but you were talking about being in fourth grade in math class and filling your math composition book with your horse stories. And, and then you made the comment. I’ve always been a writer. And I love that so much that you are acknowledging that your fourth grade self was just as much a writer as your adult published self.

Yes. Right? Yeah. Yeah. I mean, it’s just always been part of my particular makeup. I think that’s so important, like for, for kids, especially to hear and to realize that, you know, this, this dabbling you did as a 10 year old, 11 year old, you know, you’re a writer.

Right, right. Yeah. Yeah.

Yeah. I mean, I think for, and especially for art forms, like, you know, like writing and writing is very much an art form in the same way that music or ballet or painting or whatever.

And I think people who end up doing an art form seriously are people who are just driven to do it. And it’s, and it’s just what they do sometimes without even thinking, without even making a conscious decision, you know, like I’m in math class. How did I, how did I end up in the middle of this horse story? I don’t even know. I just started doing it.

And I mean, I have friends who are visual artists whom I knew in elementary school and they’re drawing was the same way. I mean, I had a friend who to this day is an artist and designer and her notebooks were just full of drawings. And, you know, she and I were probably making about the same grades. Her notebooks were just like illuminated with these illustrations all around them. And it was just like how she thought. And, you know, I guess what I would say to a child is, you know, if you have this compulsion, that’s probably a good thing. And it’s probably telling you something about yourself.

Like maybe you should also do your math homework. I’m not proud of not having done my math homework, but it’s not like the thing that you do just kind of compulsively because somehow it makes you feel more alive. It’s not like that’s less than, it’s not like that’s less important than your schoolwork. It’s not like that’s something you should be ashamed of or feel like you’re misbehaving because you’re doing it.

I mean, that’s actually probably a key to something that’s going to be really important to you in your life and something to listen to, and, you know, not encourage parents the same way. I, you know, and especially in homeschooling where, you know, your, your like default setting is to want to turn everything into a lesson.

So like your kid is writing a story and what you want to do is correct the grammar and the spelling. And rather than saying, wow, you wrote this story. That’s amazing. You should keep writing stories. Don’t be afraid. You know, that sometimes we just have to trust them and their compulsion to do these things and not try to like, take over their process. I love it.

Well, Other than the brevity. Yeah. Right. What led you to pursue writing poetry? Was there something about poetry that just spoke to you?

Yeah. I mean, I started writing poetry in the ninth grade and I really hadn’t before. Although, I mean, my parents had always read us rhymes.

I was very blessed to have a family where my parents did a lot of reading aloud and they did read us poems as well as stories. And so I’d always had homes in my ear and we always read poems in school. We had to copy poems and illustrate them to hang on the wall for Halloween and Thanksgiving and Christmas. And, you know, all of those kinds of traditional elementary school things.

But in ninth grade I had an English teacher who actually was an, is still a poet. We’re actually still friends. We kind of rediscovered each other. I went looking for just a couple of years ago and found her on the net. And she is still a poet.

She has a new book out too, but she was the first person I had ever met, who, I mean, aside from being a really just energetic, fantastic teacher, meeting her and hearing her talk about poets that she knew and had studied with. She had also, she had gone to Vanderbilt where I also went to college and had studied with the Southern agrarian poet, Allen Tate, who she, he actually died the year that I was in ninth grade and she used to go visit him in the nursing home. And this was the first intimation that I had that poetry was something that living people actually did. Like it was a thing that people did. Yeah. Right. It didn’t just like grow on the pages of your literature textbook, you know, like people actually did this.

And I mean, I read E.E. Cummings for the first time that year. And his poems were so different with all the, you know, lowercase letters and the funky syntax and all of the things that he did. I mean, it was just so startling and strange and different from anything that I had ever encountered.

And I, I think I just wanted to do that. So the first poems I wrote were like E.E. Cummings, imitation poems, but that was when I started writing poems and really shifted from writing stories to writing poems. And, and I, again, I was extremely blessed in my education, even though, even through high school, I was not a very good student.

I scraped through a lot of classes, but I loved English. And I had very good English teachers who made us read a lot of poetry. And, you know, we read things. I mean, in 10th grade we read Beowulf and Chaucer and Paradise Lost and, you know, and I just can remember, I can’t remember like exact conversations or what lines or phrases or anything took the top of my head off, but I can remember sitting in my seat in the back of the class where I sat, because I didn’t like to be called on and just thinking, this is amazing. Like suddenly I was alive and which was not a feeling I usually had at school. And, and that just carried. That hasn’t stopped.

I love that this is some school I can get behind none of that math stuff,

Right. Well, I did have to take math. I just scraped through that, but I was very lucky in my English teachers.

Well, do you believe that everyone can be a poet? Is this something that we could do with our kids in our homeschool?

Well, I mean, no and yes. I was thinking about, about this question and I mean, I wonder if we asked this about other art forms, you know, do we say, can everybody be a concert pianist? Can everybody be a ballet dancer? Can everybody be a painter? And I mean, the answer is sort of like no and yes.

I mean, everybody who takes piano lessons, isn’t going to be a concert pianist. And everybody who takes ballet lessons, is it going to be a dancer and everybody who takes art lessons, isn’t going to be a painter or a sculptor, but that’s not necessarily why we do those things. Part of the reason why we have our kids take piano or ballet or art is that it is part of their discernment about, you know, education is about learning to be, you know, learning, to discern who you are and what your calling is in life. And art is part of that. And you don’t know whether you’re going to be good at something, unless you try to do it. So that’s one, you know, I mean, like when we sign our kids up for these lessons or we try to have them do one of these art forms, you know, that’s part of what we’re thinking, isn’t it? I think, you know, that we’re thinking, well, who knows? You might discover something that’s, you’re really good at that you really love, and you won’t discover it if we don’t do it.

I think we probably also introduce these things to our kids because learning at least the rudiments of how to do something is how we can understand that thing from the inside. Like, for example, I am totally not a dancer. I was like the world’s clumsiest child. I am not. I don’t really dance as an adult, but at my girl’s school from first grade through sixth grade, every week, one of our PE sessions was ballet. And we actually, I mean, we had real dancers teach these ballet classes and it was something that I knew pretty early on that I wasn’t very good at.

I knew it wasn’t going to be a ballet dancer, but it was fun first of all, whereas PE was not very fun, kind of like math. I wasn’t very good at it.

You’re a woman after my own heart.

I know like, what is key it’s that hour where you get hit in the face with a ball that’s PE. Or you fall down or something, but ballet was fun. And, you know, because it had music involved and the movements for graceful and everything. And I think, I, you know, I was just reflecting on the value of this, that I was not going to be a dancer. It was fairly evident to me.

I didn’t love it enough, first of all, and I wasn’t that good, but learning the rudimentary of ballet over the course of six years and, you know, the basic, the five positions and things that you do with your arms and the terminology for things. And occasionally we would watch, you know, like we’d watch clips from the Nutcracker. We even see these things.

And I’m really grateful to have had that experience because even though I’m not a dancer and it was pretty clear from the beginning that that was not going to be my calling. I have the kind of appreciation for what dancers can do, because I understand some of what they do. You know, like what I did one hour a week, you know, a real dancer is doing four to six hours a day at the barre. And, you know, you start to have some appreciation for how hard it is and the discipline that goes into it and how it works so that when you watch it, your appreciation of it is, is enhanced by that.

And I think the same thing is true of poetry. It’s an art form, like dance and piano and visual art, but it’s something that everybody can try. And I think it’s good to try to try on poetic forms, to, you know, to try to write some poetry. And the point is not like you’re just going to produce this great poetry right off the bat. But I think that helps you understand what goes into poetry. And I think doing it makes you a better reader and appreciator, and it certainly doesn’t hurt your writing. I mean, it’s a form of writing that you can practice and it’s going to benefit any kind of writing that you do. So, you know, I mean, relatively few people are probably gonna love doing it so much that they can’t stop doing it, which is kind of the definition I think, of, of a poet is just somebody who can’t not do it, who works to master the form to the extent that their natural gifts allow them to do, but everybody can try it and everybody will benefit from trying it. So that’s my long answer to that.

No, I love it.

I mean, that’s, that’s a hard question and you want to go, yes, everybody has an inner poet. And I mean, I think everybody does poetry and their soul too, you know? I mean, that’s why poetry speaks to us.

Well, I loved your definition of a poet is a person who can’t help themselves.

Yeah. Right.

Why else would you do this? Like you could be vacuuming. Why are you doing this? I also love the idea that, you know, we’re going by practicing this. First of all, you know, we never know. We never know if we like fishing until we go fishing. We never know, you know, so you never know, at least give it a try, but then also, even if you’re never going to be a poet, you are going to strengthen those other, those other writing skills all the way around. You’re going to dive off into language and really appreciate words in a new way.

Right. Absolutely.

Yeah. Yeah. So if I’m a little bit convicted by what we’ve just talked about, Sally, and I’m thinking, not having my kids write some poems, how do I get started with that in my homeschool? Especially if I feel inadequate The task?

Well, I think the first step really is just to read a lot of poems. And, and when I say read poems, I mean like nursery rhymes with your little kids. I mean, I was thinking about this too. I mean, really, I think I’ve been teaching poetry to my kids since they were born.

And the earliest form of it for them is, you know, like bouncing them on my foot, going, “Ride a cock horse to Banbury cross to see a fine lady upon a white horse.” And I’m bouncing them in time with the rhythm of those lines. And they’re, so they’re feeling the meter, which is the rhythm of the poem. And they’re hearing the rhymes and they’re getting that.

It’s like getting under their skin from the very beginning. People are intimidated by poetry because they think they have to do a lot to make it happen. And the truth is you don’t, you don’t have to do any more to make poetry happen in your home. Then you do to make stories happen in your home.

You don’t have to worry about it any more than that. I mean, there are some hard poems in the world, but you’re probably not going to be reading them to your five and six year olds any more than you’re going to be reading, you know, James Joyce’s Ulysses aloud to them. I mean, you know, there are like difficult stories out there too, but we were fairly aware that there are other chapter books that we can read besides like Ulysses, right. We’re not intimidated by the idea. And I think we kind of have to get our minds in that place where we say, yeah, there are some hard poems out there that I can’t understand. And there are hard poems out there that I don’t understand.

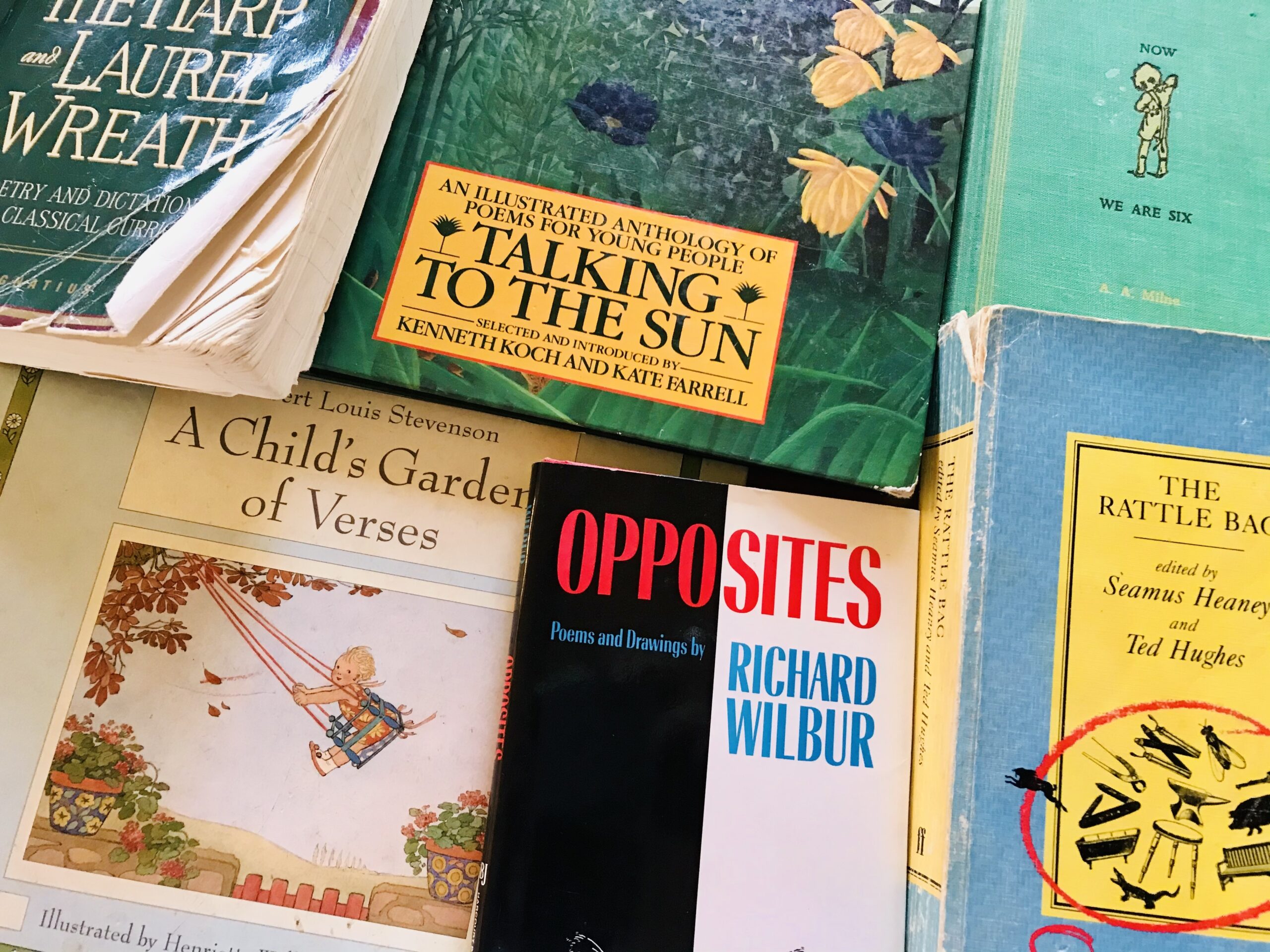

So, you’re not alone. The world is full of poems that are just fun. And just making them a part of your family culture in the same way that you make any other read aloud, a part of your family culture is I, you know, I think the first step and things that I read with my kids from really early ages. Nursery rhymes, Mother Goose, AA, Milne. When We Were Very Young, Now We Are Six. I mean, we still speak in lines from those poems, Robert Louis Stevenson and a child’s garden of verses. And another real favorite of mine is the American poet, Richard Wilbur, who was kind of an elder statesman in American poetry until he died several years ago.

But he, I think these are collected now in a single book, but he has books of poems based on a game that his family used to play. He and his wife had four children and they used to play this game at the dinner table where one person would think of a word. And then everybody else had to think of the opposite of that word.

And whoever like had the best or most creative opposite for that word won. And so Wilbur wrote several books of little poems. I mean, I’ll just like read you one here’s one, that’s just two lines. “What is the opposite of baby? The answer is a grownup maybe.” And he illustrated them with these funny little line drawings, you know, “The opposite of doctor. Well, that’s not so very hard to tell a doctor’s nice. And when you’re ill, he makes you better with a pill. Then what’s his opposite. Don’t be thick. It’s anyone who makes you sick.” You know?

So I, you know, I raised my kids on these because they’re so funny. Our favorite one is, “What is the opposite of string? It’s Gnirts which doesn’t mean a thing.” So it’s string backwards. Yeah. So

my kids would love those.

Yeah, mine did. So, you know, I mean, we just read poetry and I actually, I really have never made my kids write poetry. I don’t, I don’t know if any of the, I have, I have one son who’s a fiction and creative non-fiction writer and I didn’t make him write fiction.

He just started when he was about 15 writing 500 words a day, which I didn’t know until like last year that he had done this. But so I, you know, I guess, because I’m kind of self-conscious, I mean, they are always, they’ve all always been like, no, that’s your thing, mom. Sorry. You know, so I haven’t wanted to be too overbearing about it, but just giving them poems. And you can say, I mean, like if you want to be more proactive than I have been about it, I mean, you can say, I, you know, I certainly had them copy poems for their, you know, copy work all the time. So they were, you know, internalizing a lot and you can have people write imitations of poems that they like, you like this poem, you know, see if you can write a poem that sounds like it. And they might, I mean, a little kid is probably just going to copy the poem and that’s fine. That’s kind of age appropriate.

Right.

But I mean, imitation is a great tool. You know, you think about all the art students who go to the galleries and they sit in front of the old masters paintings and copied them.

And that’s how they learn techniques. So, you know, you can do that with poetry too. You know, you can say something like let’s notice, and I wouldn’t do this with really little kids. Like I would really just read and enjoy it. It’s really little kids, but like say you have kids in upper elementary school and you’re reading a poem that I don’t know.

I’m trying to think of a good example. You know, a poem that has a particular rhyme scheme. I mean, I tend to really love rhymed and metered poems. Cause they’re fun to read out loud and they’re easy to imitate. And you could say something like write a poem that has this rhyme scheme, you know, write a poem that uses these five words.

You know, things like that are really good starter assignments. If you want to have somebody, you know, try writing a poem. I mean, Charlotte Mason with her sort of secondary level students used poetry as a form of narration to, I mean, she might ask for, you know, a poem as a narration of something and maybe she’d give some guidelines. Like it has to have an AB AB rhyme scheme, or it has to be eight lines or, you know, she gives some parameters which really helps. I mean, I find that that’s a lot better than going, you know, write a poem about winter

and just do whatever you want.

Right. Right. That’s like, you know, go for a walk where there aren’t any street signs. You’ll have no idea where you are, but it’ll be really fun. You know, I, I usually, I mean, for myself, this is true, you know, poems don’t really start with ideas. They start with language. So giving somebody some rules having to do with the language that they use, like you have to have, I mean, this is why haiku and things like that are so much fun. Cause it’s counted syllables. And so to say to somebody, you know, write three lines and one of them is going to have five syllables and one of them is going to have seven syllables and the next one’s going to have five syllables. They can do that.

And I mean, it’s funny how, when you’re concentrating on a rules like that, it’s like doing Sudoku or something. You’re trying to work out a puzzle basically, but it’s like you trick your subconscious mind into saying things that you couldn’t have made up if you were trying to, I mean, I’ve seen this happen time.

And again, I’ve given these kind of crazy assignments where they have to write five lines and every line has to have eight syllables. And the second and the fifth lines have to rhyme with each other, you know, things like that. And so they’re just going eight syllables, one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, you know, they’re, they’re, you know, writing and counting syllables and stuff comes out that surprises them.

So you just make up your own poetic forms.

Sometimes. I mean, you can, and, and you know, and poets have often done this. If you’re thinking about resources for moms, I mean to a great extent, you don’t really need anything other than books of poetry. And I can, you know, I can sort of list anthologies that I think are good to have and authors that I think are good, but you know, for the mom who really wants to understand poetry, writing more and maybe to engage with it a little bit more with high school students, things like there’s a little collection of essays on poetry writing by a poet named Richard Hugo who taught at the university of Montana and died in 1980. So he’s been gone for a pretty long time, but this book is called The Triggering Town and it’s just it’s lectures that he gave to his classes. And there’s one where he’s talking about having, you know, himself as a student of a poet named Theodore Rettke, who’s very, was very celebrated. It was kind of his Forerunner and teacher who would give them exams that were just like, you have one hour to write a poem. And then he would get these crazy rules, like, you know, so many lines in the stands of so many syllables in every line, you know, lines three and five have to rhyme with each other and you have to use the word stone somewhere in it, you know? So there would just be these crazy rules. And in an hour they would have to come up with a poem. And I mean, that’s probably like if you want your high school student to have a nervous breakdown,

that sounds like a great idea can adapt like that. You know, you can give them more than an hour. You can make it less hard,

And, You know, as you were talking about this, I’m, I’m sitting here thinking, and if I were to look, I have one child who might rise to that occasion, you know, the other two would probably just completely melt down in they’re various ways.

Right.

But If I pulled out a whiteboard and a marker in Morning time and said, Hey, let’s do this. And it was all of us together. I think they would love it. I think they would have fun with it.

Absolutely. And I’ve done this with groups of kids, school kids where, you know, I’ve had a whole class and we’ve had, yeah, we’ve had the white board and I’ve had things like, you know, 50 index cards, each one with a word on it and we’ve randomly picked five words and we have to use them for example. And maybe we’d said, you know, and I mean, sometimes that’s the only rule, but you know, like by line three, we’ll realize we have a rhyme scheme going. And so I’m always going, look, this is happening. So what do we want to say next? This is telling us where we can go in the next line and yes. With a group of kids where no one person is on the hook to produce something wonderful. Yes. That is absolutely so much fun and they really do like that. And you, and you see the process happening on the whiteboard. And I mean, yeah, that would really be the ideal situation, as far as I’m concerned, you know, that otherwise a kid who’s going to write poems is going to write poems and I’m not sure, you know, like I don’t want to stress out a kid who really doesn’t, you know, I don’t want to give somebody a PE experience about poetry, you know, like here’s where you get hit in the face with a ball kid.

There’s so much in the modeling too, you know, it’s their ideas aren’t coming. It’s okay to throw your own in there.

Absolutely. Yeah. And yeah. And to give them the seed of an idea somehow, which is what these prompts are good for, you know, like here’s five words that you’re not going to have to make up, what are we going to do with them?

Right. Okay. So in the Thomas household, there was never like, okay, it’s time for this year’s poetry unit.

We’re going to sit down and we’re going to first learn how to write a haiku. And then we’re going to learn how to write an Italian sonnet, and then we’re going to learn, you know, so that didn’t happen. But it really, really enjoying the poetry.

Yeah. Yeah. Basically that’s always been my, you know, my primary aim and we have always done it from the time they were young and we read it aloud.

Now they get, well, it varies depending on the term, but we’ve been through high school. I mean, we’ve been reading our way through the English poetic tradition. And so usually they have one to two poems a week to read. I do have them narrate them. I usually give them background, you know, some background context to help them understand what’s going on.

We really don’t do a whole lot of analysis. Although, one thing that I do do with my high schoolers, this last set, I did this junior year. There is a book which is available in a million like editions, and it’s really easy to find used. It’s really easy to find cheap Laurence Porrines Sound and Sense which dates from the 1960s,

Laurence Porinne was a professor at SMU in Dallas, you know, sort of in the mid 20th century era and sounded sense. I, it was like this life changing book for me as a high school senior it’s it is about poetry to that handbook about poetry. It introduces poetic forms. It introduces poetic terminology. So that you’re talking about, you know, things like imagery and the relationship. I mean, it’s called Sound and Sense. So one of his great, you know, big part of his thesis is about the way that you can’t really separate the sound that a poem makes from the sense that it’s trying to get across and, and Porrine himself.

I don’t really know if he was a poet, but he’s, I mean, it’s, the writing is really kind of marvelous. He’s kind of curmudgeonly. There’s a whole section on like good poetry and bad, which I learned really fast when I was at high school teacher, not a, not a hit because everybody loves the poems he thought were bad and trying to explain to them, it’s not worth it. Really. “Sorry, you have no taste” is how to make people hate poetry. I usually don’t push that, although it’s kind of fun. I thought it was fine in high school. Cause I was just totally on board for this curmudgeon who did have ideas about excellence.

So, but I think probably everybody else in my class hated that, but it’s a good handbook to have high school students work through it’s full, every edition, the additions are slightly different, but every edition is full of good poems. So that they’re reading a huge amount of poetry. It’s one of the few times that I’ve ever assigned study questions rather than like straight narrations or discussion because the study questions are really designed to help them read the poems well, and that’s been a really, you know, it’s kind of like at some point you do kind of have to kick the conversation up a notch from just, this is about a guy and he’s thinking about death, you know, you kind of want to get a little farther than that, but yeah, I, I leave it so pretty late in the game though.

Yeah. That was my question. Definitely at the high school level, even a little into high school.

Right, right. Yeah.

Well, before we go share with me, if you don’t mind Sally, a couple, like your favorite anthologies, you mentioned you that you would talk about those and then you’ve already given us some names of poets for young kids. But if you have any other favorites that you think moms should check out.

Oh yeah, yeah. Well, okay. So for anthologies, which we’ll also kind of answer some of those favorites questions, every house, I think in my vaunted opinion that has young children should have a good mother goose, a beautiful addition of a child’s garden of verses both of those AA Milne books of poetry. When we were very young. Now we are six. I mean, they’re just so delightful to read aloud. And I mean, you can, somebody’s whole early childhood can consist of those books and you won’t get to the end of them. Richard Wilbur’s Opposites, which I think now are in a single volume and you know, are still available. I also have an anthology that I really like.

That’s more sort of like global poetry. Like it includes translations from the Yoruba people of Africa and Egyptian poems poems in that are translations from native American languages. And so it’s a very, you know, Japanese, it’s a real mix and it’s also full of beautiful art. This is a book called Talking to the Sun and the editors are Kenneth Koch, K O C H and Kate Pharrel.

And I don’t know if it’s still in print that I have seen it in used additions, but that’s a gorgeous one. If you can find it, it’s a lot of fun. It does have a lot of traditional English poetry in it too, like Shakespeare and William Blake. And just, it’s just a huge miscellany, but it’s, it’s a lot of fun and it would carry you from fairly early childhood through elementary school,

maybe even beyond. And it’s great for art study too, because it’s just got all this wonderful art in it. I’m trying to think of other favorites in terms of anthologies. There’s another anthology of world poetry edited by Ted Hughes and Seamus Heaney called The Rattle Bag, which is very good. Not all the poems are necessarily suitable for children, but it’s a great, you know, it comes in a paperback edition and again, it’s, it’s just a really great kind of world poetry anthology with a lot of translations from like the Hungarian and other Eastern European languages as well as other global cultures. So that’s another really good one to have.

In addition to the kind of classic children’s authors like Robert Louis Stevenson and AA milne, and a particular favorite of ours is Charles Causley, C A U S L E Y. He was a poet from Cornwall. He died about the time. My youngest daughter was born 2003, 2004, and wrote poems for adults as well as children. But he wrote just really wonderful children’s poems. That could be funny. They could be haunting. I mean, just a whole range. And my favorite book of his is called Early in the Morning.

So if you can find, and it’s, you probably would have to find it used, but it is out there. And it was just, it was a real favorite of you know, of my kids. And there was another book of comic poetry, which was an anthology, which again, much quoted in my family, even to this day, “Wallace trips,

Marguerite go wash your feet. And the title poem is “Marguerite, go wash your feet, the board of health to across the street.” So that’s the tone there. This is, you know, these are not poems that are going to like make you think noble thoughts, but there are a lot of fun and easy to memorize. I, you know,

“When I sat next to the Duchess at Tea it was just as I feared it would be. Her rumblings, abdominal where something phenomenal and everyone thought it was me.” You know, I have a hard time memorizing, like really serious poems, but you know, I’ll go to my grave saying that one, cause I can’t get it out of my head.

and these are great. This is how you learn, like Rhyme, meter, the way poems move the way poems look, comic poems are terrific for this. So, you know, definitely don’t be afraid to just read funny stuff and enjoy it. So, I mean, those are all just real favorites of mine. And you know, Charles Causley is kind of like the, the outlier probably that people maybe haven’t heard of. But I mean, he is my he’s one of my favorite poets period, but you know, definitely for kids. He’s a great favorite.

I love it. So many. Thank you so much because that’s so many outside of the norm that I’ve not heard of before. And so I love it. So, so many good suggestions there. And I did look while you were making suggestions and talking to the sun is not in print, but there are a number of copies available.

Great. And if, you know, if they’re like not $200,

Sound and Sense is a little trickier. Because it’s a textbook.

Yeah. Right, right. So then you have, well, yeah, like the eighth edition there, it’s easy to find copies of the eighth edition, which is old and it’s usually really cheap.

Yeah. Yeah. I, I was able to find, you know, a few of those, so yeah.

Don’t feel like you have to go with the newest edition, the textbook, Cause that’s $150 run away, but go looking for the older one sometimes old is good.

Yeah. Right, right. I mean he was in the 1960s anyway, so you don’t need the new one. So yeah.

Love it. Love it. So wow. So many good resources here and so many good ideas for how to start dabbling. And I think that’s what you definitely do. Read, read, read poetry, but dabble in some of the writing of it with your kids and see if it takes off for anybody.

Right. Right. Exactly. Exactly.

So I thank you so much for coming on and talking to us about it today.

Oh, well thanks Pam. It was great to be here.

Well, where can everybody find you and maybe check out some of your books online. I have an author website and that address is sally-thomas.com.

Awesome. And there you have it.

Now, if you would like links to any of the resources, so many resources, wonderful poetry, ones that Sally shared with us today, you can find them on the show notes for this episode. That’s at Pam barnhill.com/YMB93. Also there, you can find out how to leave a rating or review for the your morning basket podcast in your favorite podcast player, the ratings and reviews that you leave really help us to get the word out about the podcast to new listeners. And so we love it when you take the time to do that. And we thank you so very much for doing it. Now I will be back again in a couple of weeks with another great morning time interview and until then keep seeking truth, goodness and beauty in your homeschool day.

Links and Resources from Today’s Show

- Join the Your Morning Basket Community

- Your Morning Basket Plus

- Abandon Hopefully Homeschooling

- Mater Amabilis™ – A Catholic Charlotte Mason Homeschool Curriculum

- Richard Wilbur

- Ulysses

- The Triggering Town

- Talking to the Sun

- The Rattle Bag

- Early in the Morning

- Marguerite, Go Wash Your Feet

- Perrine’s Sound and Sense

Key Ideas about Teaching Poetry

- Teaching poetry to our children doesn’t have to be complicated. The most important thing to do is expose your kids to lots of poetry. So, get some great collections of poetry and read poetry to your kids.

- One thing to keep in mind when we are teaching poetry is that our goal is not to make every child a poet. We expose our children to different art forms like dance, or music, or poetry, we are because it allows them the opportunity to discover if it is something they love.

- We also expose our children to these things as a way of allowing them to appreciate what goes into that art form. Having taken the time to experience what goes into creating poetry for themselves, our children will be better writers, readers and will grow in appreciation for what they read.

Find What you Want to Hear

- 2:38 meet Sally Thomas

- 14:45 how Sally began writing

- 19:50 encouraging our children’s natural interests

- 23:20 when Sally started writing poetry

- 26:58 Can everyone be a poet?

- 33:33 writing poetry in your homeschool

- 38:30 creative poetry writing assignments

- 50:22 Sally’s favorite resources for teaching poetry

Pin

PinLeave a Rating or Review

Doing so helps me get the word out about the podcast. iTunes bases their search results on positive ratings, so it really is a blessing — and it’s easy!

- Click on this link to go to the podcast main page.

- Click on Listen on Apple Podcasts under the podcast name.

- Once your iTunes has launched and you are on the podcast page, click on Ratings and Review under the podcast name. There you can leave either or both!