Pin

Pin

Shakespeare. Whatever feelings you have about the Bard, we can all agree that he was the most influential English writer in history. But why should I bother with Shakespearean language for my littles in Morning Time? Won’t there be plenty of time for that when they are older? More importantly how would I introduce such a daunting mass of literature? What if I don’t know much Shakespeare myself? What if I don’t even think I like Shakespeare?

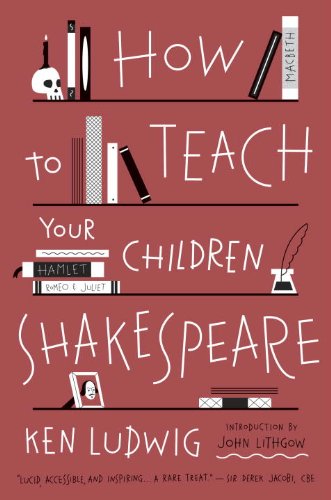

Ken Ludwig is a playwright and father who has an infectious love of Shakespeare. He began sharing his love with his children at a very young age. Recently he published How to Teach Your Children Shakespeare, a book detailing this surprisingly simple way to teach the Bard’s great works to our children.

Come and enjoy as Ken tells us why and how we should teach Shakespeare, as well as how we can handle the harder concepts. Most importantly, Ken encourages us to push past our fear and enjoy Shakespeare in our Morning Times.

Pam: This is Your Morning Basket where we help you bring Truth, Goodness, and Beauty to your homeschool day. Hi everyone, and welcome to episode 21 of the Your Morning Basket podcast. I’m Pam Barnhill, your host, and I am so happy that you are joining me here today. Well, to say that Ken Ludwig’s excitement for Shakespeare is infectious is a bit of an understatement. It’s kind of hard to talk to Ken about Shakespeare and not get a little bit excited yourself which is certainly what I did today. It was a really fun conversation that we had. So we talk about Ken’s book How to Teach Your Children Shakespeare; we dig into the method that he developed to teach his own children and that you can use to teach yours, and then also we dug a little bit deeper into the why it’s important to teach Shakespeare, how to handle some of those more difficult parts, and is there any virtue to be found to hold up to our children in the Bard’s plays. And I think you’re going to be pleasantly surprised with everything that Ken had to share with us. It’s a wonderful interview, so sit back and enjoy.

Ken Ludwig is an internationally acclaimed playwright, a Shakespeare aficionado, and the author of the book, How to Teach Your Children Shakespeare. He holds degrees from Harvard, Haverford College, and Cambridge. Ken has written 22 plays and musicals and has had six shows on Broadway and seven in London’s West End. His work has won numerous prestigious awards including two Tony’s and two Lawrence Olivier awards, which is England’s highest theatre honor. His plays have been commissioned by the Royal Shakespeare Company and the Bristol Old Vic. In How to Teach Your Children Shakespeare Ken draws from his experience of introducing his own two children to the Bard through memorizing passages and talking about characters and storylines. He joins us on the podcast today to discuss why Shakespeare should have a place in Morning Time. Ken, welcome to the program.

Ken: Well, thank you very much. I’m thrilled to be here.

Pam: We are so excited to have you. It is always wonderful to speak with somebody who is so passionate about their topic, and you really are.

Ken: I really am! I am thrilled to be here, partly to talk to you, and partly to talk about my favorite subject in the world which is Shakespeare, especially kids learning Shakespeare from a young age.

Pam: Well, do you remember your earliest experience with Shakespeare? What made you love him as much as you do?

Ken: I do, actually. When I was a boy, I was about 10 years old, I think, my parents a few years earlier than that had been to New York, had seen the famous production of Hamlet with Richard Burton and when it rolled around to be my 10th birthday some years later they got it in their heads to buy me the recording of that production of Hamlet with Richard Burton. It was an LP recording, those old discs, and they gave it to me for my birthday and I started listening to it and listened and listened and listened, and I just loved it. I fell in love with, I guess, his voice – Richard Burton being one of the great Shakespearian actors of all time – and I fell in love with the material itself and I ended up memorizing large chunks of it, all of the soliloquies and other parts of the play. I literally wore those vinyl discs down until they were useless. I actually have since bought another set, which I could get on E-bay. And so I just fell in love with Shakespeare and started seeing it as much as I could and started reading as much as I could.

Pam: So, do you think that this love, this early love that you developed for Shakespeare at about age 10 was, kind of, pivotal in your decision to go into the theater and acting?

Ken: Absolutely. I remember going to the theatre when I was a youngster, too. My mother’s family lived in New York and when we would visit my grandparents, every year we would go see a Broadway Show, one Broadway Show a year, it was a big treat. And even when I was six years old I remember very well going to the theatre and at the time thinking, ‘This is what I want to do. All I want to do is be in the theatre for a living.’ And then Shakespeare got me and I was really hooked.

Pam: Let’s talk about your own children for a minute. What about their experiences with Shakespeare? As a parent did you always know that you would want to introduce them to Shakespeare early, or was there a moment when you realized, ‘Hey, this is something I want to do, I think it’s a good idea to start when they’re young.’

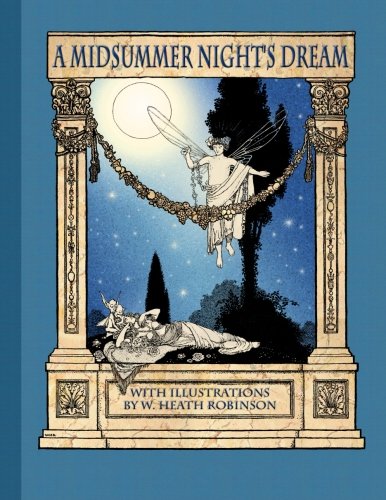

Ken: Well, it took me by surprise. I never thought about teaching them Shakespeare per se, I loved it myself, they were growing up, and the older of the two kids, my daughter Olivia, reached first grade and came home one day from school and said, “Daddy, I know a bank where the wild time blows.” And I was just rocked off my feet because that’s a line from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and I said, “Where did you learn that, Olivia?” and she had learned it in school. Her teacher was an English woman who loved Shakespeare and decided it was never too early to start teaching kids a little bit of Shakespeare, that they could memorize it easily. And indeed she knew about four or five lines by the end of that week that her teacher was teaching her. And that’s when a light bulb went off in my head and I thought, ‘I love this stuff so much myself and why don’t I try to teach her some Shakespeare. She’s 6 years old, she’s got an open mind, she’s not afraid of it yet which is a plus because kids as they get older and adults all over the world (we’ll talk about that in a few minutes) think Shakespeare is daunting. It sounds confusing when you first hear it. But when you’re a youngster, a just have an open mind and you lap it up the way you would a nursery rhyme. So, after her teacher taught her these first few lines, I thought, ‘Ooh, I’m going to try this.’ So my experiment was that she and I would snuggle up together, open a book (is what I started to say) but I did better than that, what I did was I typed out on my computer whatever I wanted her memorize and I did it in very large type, she was just learning to read at the time, in an attractive font, I used Comic Sans which is easy to read and fun to read, and I think at 20pt, and I typed out “I know a bank where the wild thyme blows, where oxlips and the nodding violet grows, quite over-canopied with luscious woodbine, with sweet musk-roses, and with eglantine.” So those four lines which are four lines from A Midsummer Night’s Dream and it’s when the Fairy King, Oberon, is telling Puck, his mischievous second in command, where to Tonya (the Queen of the fairies) she sleeps, this bank of flowers. And that description of flowers is so beautiful. I typed those four lines out, those are the ones she had learned at school, and we went over them, and she knew them pretty well, and I explained to her what certain words meant, that she might not otherwise understand. It’s really – you know, you have kids – and presumably everyone who’s listening to this podcast has kids and knows that when they are young and their minds are open, and they’re smart, they’re all smart, and if you explain to them very simply what the situation is, and then I would word by word, phrase by phrase, and line by line, teach her the lines – those first four she knew from school, and then that particular group of lines is 10 lines long and it’s the first passage in my book. And it’s a great one to start kids with and she learned all 10 lines in no time at the end of, I’d probably say, virtually at the end of that hour together (we spent one hour on Saturdays and one hour on Sundays) and my theory developed was that the best way for kids to learn Shakespeare was to memorize it. I think memorization has taken a bit of a hit in modern education and I don’t think it should. I think memorizing poetry is a great way to make kids familiar with the sound and the meter of their favorite authors and to really embed it in their heads so it becomes a part of them. And so I started teaching her passages from my favorite plays and she really took to it. And that’s how I fell into teaching my kids Shakespeare.

Pam: And then this is the method, this very same method – and I have to tell you that we have really latched onto this, I think it took my kids less than two weeks to memorize that first passage – and then we were doing a poetry tea party with our friends, and that was the passage my son chose to recite at the party.

Ken: Oh great!

Pam: You’re right, their minds are so open and receptive and never once do they look at you and go, “Mom, I can’t do this!” They just do it.

Ken: They do. Exactly, they just do it. And they love it. It’s fun, they feel a sense of accomplishment. They can see that their parents are proud of them. And often, early ones I chose are rhyming couplets. It’s easier because you’re always moving towards the rhyme, “I know a bank where the wild thyme blows, where oxlips and the nodding violet grows…” so that’s kind of like a nursery rhyme.

Pam: Yeah, it really is. And just the rhythm of the words and then we’ve taken, kind of, phrasing method that you’ve used, you’ve broken down all of these Shakespearian lines and they are printables available on your website where you’ve broken them down into the phrases, and we have actually started using those for other pieces of memory work that we want to memorize as well.

Ken: Oh good.

Pam: Breaking down these poems into these natural phrases within the poetry. But, tell us about your book. This is what you’ve done- you’ve taken this method that you’ve used for all of these years to teach your children and you’ve turned it into a method that now I, as a parent, who might have this fear of Shakespeare, can use myself easily with my children.

Ken: That’s exactly what I’ve done. And the book is two-fold, I think, in that way you describe it, which is it is, first of all, the message of the book is very simple and clear which is: don’t be afraid of Shakespeare. The underground trick of the book is that it’s actually as much for adults as it is for children because so many of us, and my friends who are in theatre, which is most of my friends, look on Shakespeare as something a little frightening and the notion of the book is that it needn’t be. It is a foreign language, don’t fool yourself. There’s no reason to think you would hear Shakespeare and be able to understand it and speak it right away. Treat it a little bit like a foreign language. Imagine if you heard a play in Italian, and you didn’t speak Italian? You wouldn’t know what they meant in those first five minutes, but if you started to learn Italian and learn a word at a time, and a phrase at a time and memorized a bit, it would start to become clear. Well, Shakespeare isn’t as nearly hard as a real foreign language. It’s mostly accessible, 80% of its accessible right away. But because it was written 450 years ago, and because words have changed over that time, some words we don’t use anymore, some had slightly different meanings, it can seem a little confusing. Message one of the book is don’t be afraid, embrace it, open your mind, Shakespeare is not only fun to do, is not only great to do with the kids, but the fact of the matter is Shakespeare is the bedrock of western civilization in the English language. It is absolutely what you need to know if you’re going to be an educated person in our society who uses it to open the gates of all the rest of literature, because all of literature since Shakespeare is somehow based on Shakespeare. Jan Austen and Charles Dickens and Charlotte Bronte and Henry Fielding, right up to modern authors. Ian McEwan and all the good novelist and prose writers of today know their Shakespeare and base things on Shakespeare, base stories and their phrasing and you need to know Shakespeare if you’re going to be a really intelligent person in our society and open those gates to literature. That’s the message of the book; open your mind to Shakespeare, it’s easy if you take your time and follow the method. So the second part of the book is this method, and the method grew out of teaching my daughter. I had no idea in the world that I would ever write a book about it. I had no idea in the world that I was really evolving any method or anything new. But in trying to impart my absolutely love of this language and love for these stories so much a part of my own being in wanting to share it with my children, what it evolved to was pretty simple, which was “ah, wait a second, I’ll break it down into short passages, start with the ones that are most accessible to children (usually the ones from the comedies) and have them memorize these short passages. And by memorizing them, these become part of their body language. It just becomes part of them. So when my daughter went off to college she was able to take to college with her about 1000 lines of Shakespeare that she could just rattle off, admittedly, I got really enthusiastic about it, so we continued to do Saturdays and Sundays from age 6 right through 16 or 17. I mean, yes, it became harder as she was on the tennis team and doing this and that and the other and we’d have to really say, “OK, this is Shakespeare time” and did we miss a couple of times when she got as old as 14, 15, 16 – now and then – but not too many because we loved doing it. It was a special time together and she loved it, and she just loved learning the stories and saying the words. And she knew it made her special, so she literally, to this day, can rattle off hundreds and hundreds of lines of Shakespeare.

Pam: I think this is one of the wonderful things about the book and the method that you’ve put forth here is that it didn’t grow out of this desire that you had to make your kid the smartest or turn it into some parlor trick or something like that, it grew out of a desire that you had to share your love for something with your children and I think that’s what makes it a wonderful approachable method that parents can use.

Ken: Well, thank you. That is absolutely true. And I don’t think if I had wanted to make it, I like the way you put that- like a parlor trick or a way to smarten them up, I don’t think I’d have succeeded, because first of all, I don’t think I could have informed myself about a subject that I didn’t love and I don’t think I could have imparted it to my children the same way. This was just to share something I love. And let me say, most parents who will read this book will not already have the background I had in Shakespeare, I taught it to myself, but it was just my quirky own particular interest and love, because I’m a playwright and I love language, but it’s easy to do and the trick is to stay ahead of the kids just a couple of pages, not even a whole chapter. If you’re a parent, and you go, “OK, listen, I don’t particularly know my Shakespeare too well, let’s start with this first chapter. Ken tells me that I’m going to teach them these first two lines of this passage by Oberon, the King of the fairies.” If you spend time with the first two pages or three pages of the book and learn them yourself you’re ready to start with the kids.

Pam: Right.

Ken: Because you’re ahead of them.

Pam: And you do lay it out there for us and explain a lot of the little nuances of the passage that we’re learning and what the different words mean and why they’re fun or why they’re important and give us that background knowledge that we need, for those of us who might not be quite as knowledgeable about it there.

Ken: Thanks for saying that. And that’s exactly the idea. And having it tied to the stories is so important. The first of the plays that I focus on is A Midsummer Night’s Dream which is about the fairyland and lovers who escape into a magic wood that is very accessible and the second one is Twelfth Night my own personal favorite among the comedies along with Much Ado About Nothing. And I just opened the book — I have it here next to because I knew we’d be chatting so I just grabbed a copy off my shelf – I just opened it randomly and I’m on chapter 14 on page 83, if you have it handy, and it is the beginning of the discussion of passage 7, the nature of Shakespearian comedy. So I lay out the story of Twelfth Night and the story opens with a young woman (this is the second scene) who’s washed on shore in a country she’s never been to, she thinks her twin brother who is on the voyage with her has drowned. Her name is Viola, her brother’s name is Sebastian. But in the gorgeous opening of this scene, it’s very, very simple, and how it somehow magically reels us in to this woman is almost beyond description. It’s hard to describe. In the previous scene we have heard a man, who she’s going to fall in love with later, named Orsino, use really big, highfalutin language because he thinks he’s in love with someone and he says, “If music be the food of love, play on, give me excess of it, that surfeiting, the appetite may sicken, and so die.” So he’s, kind of, full of himself and he’s full of beautiful purple language, and in the very next scene which is 20 lines later, all that happens is this lovely open young woman named Viola gets washed onshore and her opening line is, “What country, friends, is this?” and the captain says, “This is Illyria, lady” and she says, “What should I do in Illyria? My brother, he is in Elysium. Perchance he is not drown’d: what think you, sailor?” and the captain says, “It is perchance that you yourself were saved.” Well, that’s one of the passages I suggest that kids learn. It’s a little dialogue between these two people and it’s just so simple and it’s self-explanatory, but somehow, in his absolute genius Shakespeare manages to catch her simple open heart, her love for her brother because this whole play is about the love of a brother and a sister, and they look for each other throughout the whole play, and so in those four simple lines we’ve really captured the essence of the whole play. So it gives us a basis to tell the story of the play to our kids. And as I say, my kids just love this stuff.

Pam: I think some of the genius in Shakespeare is how he manipulates the language to, in the way people speak within the plays, that tells you about their character. It’s not just what they say but also the words that they use and how they say it and the kind of language they use. I’m thinking of even characters that were slightly confusing like Caliban in The Tempest where sometimes he’s in iambic pentameter and sometimes he’s in prose and you’re trying to figure him out.

Ken: That’s very astute of you to say that. That’s exactly right. Shakespeare tells us everything in his language. And once you hear somebody speak, you kind of, get a really good sense if they’re good-hearted, if they’re evil, if they’re plotting, what they’re up to, and that’s really smart of you – that’s exactly right.

Pam: Well, let’s talk about some of the challenges that some families might have with Shakespeare that go beyond the fear. So, if I’m over my fear of Shakespeare, a little bit, and I’m ready to maybe work on some of this with my kids – now, you’ve told me that one of the main reasons that I should study Shakespeare with my children is because he is the bedrock, or the foundation, of all western literature since his time. So, do you have any other reasons why we should push past some of these fears and difficulties and study Shakespeare?

Ken: I do. I think certainly one of them is as simple as increasing our vocabulary, learning how to read literature. Literature of any age that predates us in a significant way, let’s say Dickens or Austen, is not readily, it’s not as easily readable as Harry Potter and it’s because it was written 100 or 200 years ago, so reading Shakespeare teaches us how to read literature. It also teaches us really good moral values as does Dickens. I keep going back to Dickens and Austen and Bronte, but as do most major authors, they’ve thought very hard about life and they’ve thought through problems that we all encounter and how we face them and that’s what literature does for us, and it makes us think harder about doing unto others as you would have done to yourself, it makes you think about compassion and heart, and good and evil, and all kinds of love- the love you have for your wife and husband as well as the love you have for your children, and for your siblings, because Shakespeare is filled with stories about all these interfamily relationships. So it makes you think harder and therefore you get smarter and smarter. It just makes you smarter because you’re thinking about things that are important. To go back to the earlier part of your question, in addition to being exposed to it and fighting past your worry about your fear of it, what else can you do to help fight past that? And that’s something that I talk about early in the book, which is part of the technique I haven’t talked about yet, is making sure you, and then your kids, understand every word of each line, and therefore, every phrase, and therefore what it really says, because once you really understand what it says, you can’t really memorize until then. I’m, sort of, looking through the book right now to see a good passage to use as an example. Here’s four lines from Twelfth Night when Viola, she’s in disguise as a young boy named Cesario, he’s talking to a woman and Viola’s master wants this woman to fall in love with him, the object of affection is Olivia (my daughter’s name, by the way) and Cesario says, “If I did love you in my master’s flame with such a suffering, such a deadly life, in your denial I would find no sense, I would not understand it.” So, you can’t memorize those four lines until you really understand what each of those words means. If, as if you turned to someone and you said, “I don’t understand why you don’t love my son, if I did love you, in my master’s flame…” what does flame mean? Flame is obviously Shakespeare taking the word and using it in an original way that I don’t think has ever been used since, “if I did love you in my master’s way of loving, if I did love you in the same way my master does, in my master’s flame,” I want to suggest the word flame is fire, and someone has fire in their heart and in this case it’s the love of a man and a woman, not sibling love. So it’s, “If I did love you with the flame of passion the way he did with such a suffering, such a deadly life, in your denial I would find no sense.” Well, maybe if you were talking with a younger kid, what does denial mean? Denial means saying no to something. So until you understand all the words in those four lines you’re not going to understand the passage and you can’t really memorize it with any integrity. So, an important step in this is going slowly enough that you understand every word of the passage.

Pam: OK, yes. That makes perfect sense that you would need to have a good understanding of what’s being said in order to embody it and make it your own.

Ken: Right.

Pam: Which leads me to my next question: there are some parts of Shakespeare I’m not so sure I want my kids to understand at 8 or 9 years old. So what should I do as I’m introducing my kids about some of the violence and maybe innuendoes in Shakespeare? How do you handle that?

Ken: Two answers. One is this book particularly is gauged so that these passages, I don’t start the book with Macbeth, I don’t start it with King Lear (in fact, I don’t think I quite get to King Lear in the book as much as I would have liked to, I couldn’t cover everything) so the passages in this book are gauged so that if you use the ones that I’ve chosen, the kids aren’t being exposed to anything before they should be because I chose them carefully for my kids, because I didn’t want my kids exposed to that either when they’re 6, 7, 8. 9, 10 years old, I don’t really want them thinking about this famous, the long poem Shakespeare wrote The Rape of Lucrece. I don’t want them thinking about rape or horrible things like that at age 9 and 10 years old. And then in terms of after that, they’re going to grow and understand what they’re going to understand the way they do with everything. God knows they’re exposed to so much with television and movies. I remember my mother and dad taking me to a movie when I was a kid and later seeing them looking at each other thinking, “Oh my God, what did we do?” And I didn’t know what they were talking about because I didn’t understand the thing they were worried about me seeing. I didn’t get it, it was gone over my head, and I think kids will absorb those things when they’re ready, and I don’t think there’s anything in Shakespeare we need worry about. I mean, Shakespeare is filled with all the things that life is filled with- life and death. In Romeo and Juliet, which is one of the earlier plays the kids get exposed to, when they get exposed to it, which normally at school when they’re in maybe 7th or 8th grade, when you’re in 8th grade you’re 14 years old, right? When you’re 14, 15 years, you’re going to learn about the sad realities of death in Romeo and Juliet, the tragedy does revolve around the deaths of Romeo and Juliet, and when they’re ready to take that in, I wouldn’t be using that with my daughter when she’s 7, 8, 9, just because they’re not going to understand it in any profound way, but by the time they’re 14, 15, and 16, they probably have almost certainly lost a grandparent and may be seeing things that makes that reality have meaning to them. When they’re little that doesn’t have any meaning to them. Then it’s appropriate.

Pam: So we’re just going to, kind of, drip out the full content of Shakespeare over the times that it’s appropriate for them to finally come to realize those later plays that maybe a little deeper and darker and have more things in there that are suited to older children?

Ken: Absolutely. I think approaching Shakespeare, choosing the right material to make it age-appropriate for the kids is very important.

Pam: I took my daughter, oh goodness, it was almost two years ago now, so she would have been 8½ or 9 years old to a local university production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream and there were a few moments where it got a little racy there, Titania and Bottom had gone off together and there was a little bower set up and the fairies were doing their silly thing around there, and it completely went over her head.

Ken: That’s exactly right, that’s exactly it! You go, “Oh well, why shouldn’t they be sleeping together, mom? We all sleep. We all take a good nap together.” Yeah, absolutely right! And when they’re ready, they’ll understand it.

Pam: I was not going to offer explanation, she was just enjoying the play for what she saw.

Ken: That’s great.

Pam: Well, you know, at Your Morning Basket our tagline is “Truth, Goodness, and Beauty for your homeschool day” so could you help me out in finding some truth, goodness, and beauty in Shakespeare? Do you have some examples of virtuous characters or eternal truths, and you’ve already touched on these with the importance of family and the relationships there and all of his examples of love and things of that nature, but do you have some virtuous characters that you could share with us from Shakespeare who we could hold up as examples?

Ken: Absolutely! Absolutely! There are dozens of virtuous characters in Shakespeare, who we love for the goodness of their hearts and we love for the good deeds they do at the same time. All the comedies I’ve been talking about are filled with those kinds of characters (not all the characters are that way) Oberon and Titania are a little spiteful with each other, the king and queen of the fairies, but the four lovers, Hermia and Helena, and Lysander and Demetrius are all good kids, they’re all good teenagers who mean well and don’t want to offend. Poor Hermia doesn’t want to offend her father but she can’t live under certain rules at the age she is. Beatrice and Benedick in Much Ado About Nothing – they’re an older couple who are in love and they’re funny, but they have such good hearts. Beatrice says at one point, “A star danced and then I was born.” It’s her way of expressing the fact that she’s good humored, that she always has a twinkle in her eye, and always likes a good laugh – those are my favorite characters. Imogen in Thimblelane is a woman of pure heart and love and saves her country as well as discovers in the course of the play, two long lost brothers who she comes to love. The comedies and romances are filled with people we want to emulate. The comedies tend to fall in to characters who are good natured and then the pompous silly characters the ones who are good natured like to show up for their pomposity, so in Twelfth Night my favorite, favorite character in all of Shakespeare, Viola, who was just talking about a moment ago, who gets washed up onshore, couldn’t be of pure heart, couldn’t be more virtuous, and in the course of her life in Illyria, the country she comes to live in, we meet Malvolio who is not a villain. He is also of good heart, but he’s teased because he is a servant and he’s in love with the mistress who he serves. He’s like the butler and she’s the woman he works for and he’s secretly in love with this wonderful woman named Olivia. So, if I was … gee, I could make a list that is dozens of pages long about virtuous characters in Shakespeare but start with Viola, start with Beatrice and Benedick, and Imogen.

Pam: Well, there are certainly some eternal truths and lessons that we can learn from the not-so-virtuous characters in the tragedies as well, I’m sure.

Ken: Absolutely. In Hamlet, Helonias, the old overly talkative, sort of chief-of-staff to the king is not himself a very good man but he gives a famous series set of advice to his son who’s going to France; it ends with “to thy own self be true and it must follow the night, the day, thou canst not then be false to any man.” And his famous advice to his son as he goes off into life, even though he’s a bit of a pompous fool, it’s a moment that Shakespeare must have decided, ‘Well, I know he’s a bit pompous, and I know he’s overbearing, and he causes trouble in the play, but I have a moment here in the play where I have a father giving advice to his child, as his child goes off into life and I’m going to give him the best 12 lines I ever wrote!’ and that’s one of the great passages in all of Shakespeare.

Pam: It’s a lovely example. One of the things that I believe about Shakespeare, personally, is that you shouldn’t just sit there with your book and read it silently to yourself. Reading it aloud yourself, memorizing passages, are all wonderful, but Shakespeare was really meant to be experienced, to be seen. So what are some qualities that parents should look for in a good Shakespeare production to share with their children? Which movies should we look for? Which, even local productions, what kind quality should we look for in that, to choose the right ones?

Ken: Go by the reputation of the acting company you’re going to see. Here, your local situation, some will be probably spectacularly good and sensitive and wonderful, and some might miss the mark, and that’ll depend on the quality of the director and the actors, and how they interpret the text, whether they’re true to it, or whether they go off on a tangent. Some of these local productions will go, “Oh, I have a new way of looking at Taming the Shrew, I’m going to set it in the wild west. (I’ve seen two or three productions of Taming the Shrew set in the wild west) and that doesn’t mean by nature that it can’t be a good production, they have a lot of heart and be interesting, but if somebody’s going to imprint something a little off the mark on Shakespeare you usually go in at least with a question mark in your mind. It’s more likely you’re going to get a good production from a company that is tried and true and overtime has served you well. When you get into the larger sphere, you know that if it’s got – I’m on the Board of Governors of the Folgers Shakespeare Library here in Washington, D.C., we do three productions a year, we’ve recorded all the productions so the Folger recordings are terrific. They’re tried and true and they’re wonderful. The Royal Shakespeare Company, or the RSC in Stratford, England has done great productions of Shakespeare for 50-60 years now. They’re just a Mecca, they were the greatest place for Shakespeare in the world for a period of about 25 years. Another equally great place now is the Globe Theatre in London. And these are not inaccessible because the RSC puts a lot of its things out on DVD, and The Globe now puts all of its productions out on DVD (started this just about three or four years ago). They have the best production ever of Much Ado About Nothing- terrific! One of The Tempest I just saw. Virtually all of the plays are available from The Globe and the RSC, great audio productions from a company called Arc Angel has done all of the plays and they’re easy to get on DVD or to stream them. And you’re absolutely right, Shakespeare was meant to be heard and spoken and seen, and that’s the best way to get to expose them. And let me add, if somebody has a Shakespeare comic book, great! More power to them, any way to get exposed to it. There are a lot of graphic novels these days, novels with drawings and less words, more drawings, and that’s fine too. Most of these people spend that much time doing something or doing it out of love and if you have the essence of the play that way for the first time, or retellings of the stories for children, that’s great, that’s great. Start there.

Pam: All excellent advice. Well, Ken, thank you so much for joining us here today to talk about your book and about your passion for Shakespeare and share this with us. And, where can people find the book and find you online?

Ken: Well, thank you for asking. The book is titled How to Teach Your Children Shakespeare. It’s certainly on Amazon and Barnes and Noble. I’m glad to say it was a best-seller on Amazon about four weeks ago, it hit one of their best seller lists and I was thrilled with that. I took a picture of it on my phone!

Pam: I bet.

Ken: Easily available in all bookstores. I was just in England two or three weeks ago and I went into The Globe bookstore and there it was, and I went into the National Theatre Bookstore and there it was. So I was thrilled with that. You can also go to HowToTeachYourChildrenShakespeare.com (it’s a lot to type out). It was published by Random House and still is, now in paperback, so they set up that website for it. The best place probably to go is my website, my own website, which is just simply KenLudwig.com and there’s links there to purchase the book through Amazon and Barnes and Noble. And, also, I encourage people, if you can, to tweet me. I’ve got a Twitter feed that is simply @Ken_Ludwig and I often post pictures of productions of my plays. A lot of my plays, as you can imagine, are based on Shakespeare. One I wrote called, Shakespeare in Hollywood that I was commissioned to do for the Royal Shakespeare Company is about the production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in Hollywood. There was a very famous production in the 1930’s with Mickey Rooney and Olivia de Havilland and I [**inaudible 40:15**] in the play that we’re back stage filming of it, and Oberon and Puck turn up (the real Oberon and Puck) and that one’s based on A Midsummer, and several of my plays are based on Shakespearian themes.

Pam: That sounds like fun.

Ken: So my website’s a good place to find those.

Pam: We will post links to all of those websites and also your Twitter feed (which sounds like a lot of fun) in the Show Notes of this episode so people can find that really easily.

Ken: Oh great.

Pam: Thank you.

Ken: Thank you, Pam. It’s been a pleasure, I really appreciate the time and I can tell you share my enthusiasm for this, so that’s great.

Pam: Oh yeah, it’s a lot of fun.

And there you have it, episode 21 of the Your Morning Basket podcast. Now, for today’s Basket Bonus, what we have for you is a little cheat sheet to help you really seek out the good themes and the virtuous themes in Shakespeare’s plays. What we have done is we have taken many of the plays that Ken talked about and has passages from in his book, How to Teach Your Children Shakespeare, and we’ve pulled out some of the virtuous themes for you. I actually have a ‘dream team’ of helpers here, my podcast manager, Mary Reiter, and her husband, Dr. Jeffrey Reiter, have worked together on this project. It’s so nice to have wonderful help like this. They have helped me pull together this list for you of some of the virtues in these Shakespeare plays so we can talk about these themes with our children as we’re memorizing these passages and hiding these words in our hearts, so I hope you’re going to find that really useful today. You can find that over in the Show Notes for this episode, you will find that at EDSnapshots.com/YMB21. Also there, you’ll find links to a number of the resources that Ken and I talked about for making Shakespeare more accessible to your children as well as his own website where you can find out more information. Also, there, if you are so inclined, there is a place that walks you through how to leave a rating or review for the Your Morning Basket podcast in iTunes, so if you would like to do that we show you exactly how. And to all of you who have already left a rating or review for the Your Morning Basket podcast we just want to say thank you so much for doing that. The ratings and reviews you leave in iTunes help us get word out about the podcast to new listeners and so we really appreciate it. We’ll be back again in another couple of weeks with another great Morning Basket interview and until then, we hope you keep seeking Truth, Goodness, and Beauty in your homeschool day.

Links and Resources from Today’s Show

- How to Teach Your Children Shakespeare

- How to Teach Your Children Shakespeare website

- Ken Ludwig’s site

- Twitter @Ken_Ludwig

- A Midsummer’s Night’s Dream

- Twelfth Night

- MacBeth

- Hamlet

- King Lear

- Much Ado About Nothing

- Cymbeline

- Shakespeare’s Globe in London

- Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington D.C.

- Royal Shakespeare Company

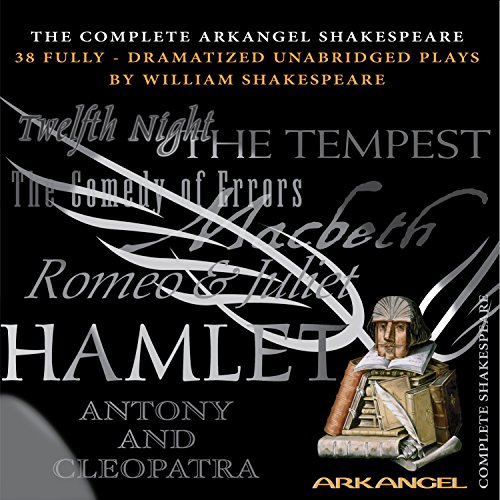

- The Complete Archangel Shakespeare

- A Midsummer’s Night’s Dream: Shakespeare Graphics

Find What you Want to Hear

- [1:15] Meet Ken

- [2:34] What made Ken love Shakspeare

- [5:49] Introducing Shakespeare early

- [10:30] Ken’s method for teaching Shakespeare

- [21:31] Overcoming Shakespeare fear

- [20:25] But is Shakespeare kid appropriate?

- [30:34] Truth, Goodness, and Beauty in Shakespeare

- [35:10] How to find good Shakespeare productions

Pin

PinLeave a Rating or Review

Doing so helps me get the word out about the podcast. iTunes bases their search results on positive ratings, so it really is a blessing — and it’s easy!

- Click on this link to go to the podcast main page.

- Click on Listen on Apple Podcasts under the podcast name.

- Once your iTunes has launched and you are on the podcast page, click on Ratings and Review under the podcast name. There you can leave either or both!